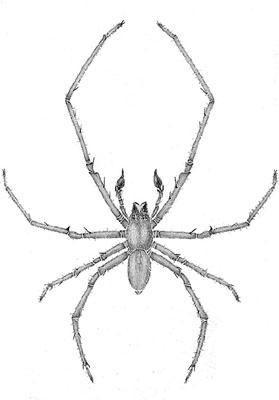

Agrarian sac spider

Order: Araneae

Family: Clubionidae

Genus and species: Cheiracanthium inclusum (Hentz)

Sac spiders are the probable cause of more spider bites than any other kind of spider, and their bites are probably often misdiagnosed as brown recluse bites by health care providers. The agrarian sac spider is pale grayish tan, with the cepaholothorax a little darker than the abdomen, and it lacks conspicuous markings. The cephalothorax and abdomen measure about 3/8 inch long. With legs extended, the spider measures about ¾ inch long. The legs are long and delicate, and they lack conspicuous spines that are discernible to the naked eye. The front legs are longer than the other three pairs.

C. inclusum occurs in South America, Mexico, the West Indies, and all but the most northern parts of the United States. It is often found on trees, shrubs, and low vegetation bordering open expanses, such a fields (Edwards 1958). It has been found in abundance in Arkansas cotton fields and in stands of young shortleaf and loblolly pines (Whitcomb and Bell 1964; Peck et al. 1971). It is also found in fields of various crops, fall webworm nests, and occasionally in man-made structures.

The spiders are active almost exclusively at night. They have a proclivity for moving through vegetation above ground level. They run rapidly over foliage and twigs, waving their forelegs before them. They can move from plant to plant on silken scaffolds, or they can float long distances through the air on silken threads (Peck and Whitcomb 1970). Adults can be found from April through November. Immatures make up a larger proportion of the population beginning in June. The spiders winter over as subadults or adults.

Sac spiders do no build snares for prey capture. However, they do construct tubular silken retreats about an inch long. These may be open at one or both ends or completely enclosed. They are placed on the undersides of leaves or under rocks. The spiders hide in these retreats during daylight hours. They wander out at night to hunt. Agrarian sac spiders prey indiscriminately on a wide variety of arthropods, including insects and spiders much larger than themselves.

As many as 30 percent of adult males may be killed and consumed by females at mating. Females mate only once. They can produce up to five egg sacs, each containing around 40 eggs. Eggs are produced in June or July. They are laid in a loose mass and covered with only a thin coat of loosely spun silk. Egg sacs are suspended in a tightly woven brood cell. The female encloses herself with the eggs, which she defends vigorously. Spiderlings remain inside the brood cell until after they complete the first molt. They have been observed feeding on infertile eggs in their egg mass (Peck and Whitcomb 1970).

The chelicerae are long and powerful, and the fangs can easily penetrate human skin. Most bites occur when people are gardening or performing other kinds of outdoor activities. When William J. Baerg wrote about this species in 1959 (Baerg 1959), he was able to offer only record of a Cheiracanthium bite in the continental United States. Since that time, many more cases have been reported (Gorham and Rheney 1968). The venom has mild and local cytotoxic and neurotoxic effects. Neither severe trauma nor deaths have been attributed to sac spider bites.

The bite is usually painful from the outset, with developing redness, swelling, and itching. A burning sensation associated the site of the bite may last for up to an hour. Rash and blistering may ensue. Some victims develop symptoms similar to those of black widow bites but much less severe: fever, malaise, cramps, and nausea. A shallow necrotic ulcer may form in the first day at the site of the bite, but it is less serious than lesions resulting from brown recluse bites. Redness and itching usually disappear after about three days, and the skin usually heals in 10 to 14 days (Sams et al. 2001).

A related species, Cheiracanthium mildei, is a Mediterranean native. It has spread throughout most of the eastern United States since it was first found there in 1949 (Bryant 1951). Although it likely occurs here, it has not yet been found in Arkansas. It is common in homes in the Northeast, where it builds its retreats along the angles where walls and ceilings meet. It has been the probable source of sharp pain and necrotizing skin lesions in several spider bite cases (Spielman and Levi 1970; Krinsky 1987).

A related species, Cheiracanthium mildei, is a Mediterranean native. It has spread throughout most of the eastern United States since it was first found there in 1949 (Bryant 1951). Although it likely occurs here, it has not yet been found in Arkansas. It is common in homes in the Northeast, where it builds its retreats along the angles where walls and ceilings meet. It has been the probable source of sharp pain and necrotizing skin lesions in several spider bite cases (Spielman and Levi 1970; Krinsky 1987).

References:

Baerg, W. J. 1959. The black widow and five other venomous spiders in the United States. University of Arkansas (Fayetteville) Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 608. 43 pages.

Bryant, E. B., 1951. Redescription of Cheiracanthium mildei L. Koch, a recent spider immigrant from Europe. Psyche 58: 120-123.

Edwards, R. J. 1958. The spider subfamily Clubioninae of the United States, Canada and Alaska (Araneae: Clubionidae). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 118: 365-436.

Gorham, J. R. and T. B. Rheney. 1968. Envenomation by the spiders Chiracanthium inclusum and Agriope aurantia. JAMA 206 (9): 1958-1962.

Krinsky, W. L. 1987. Envenomation by the sac spider Chiracanthium mildei. Cutis 40 (2): 127-129.

Peck, W. B., L. O. Warren, and I. L. Brown. 1971. Spider fauna of shortleaf and loblolly pines in Arkansas. Journal of the Georgia Entomological Society 6 (2): 85-94.

Peck, W. B., and W. H. Whitcomb. 1970. Studies on the biology of a spider, Chiracanthium inclusum (Hentz). University of Arkansas (Fayetteville) Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 753. 76 pages.

Sams, H. H., C. A. Dunnick, M. L. Smith, and L. E. King. 2001. Necrotic arachnidism. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 44: 561-573.

Spielman, A. and H. W. Levi. 1970. Probable envenomation by Chiracanthium mildei, a spider found in houses. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 19 (4): 729-732.

Whitcomb, W. H., and K. Bell. 1964. Predaceous insects, spiders, and mites of Arkansas cotton fields. University of Arkansas (Fayetteville) Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 690. 84 pages.