Squash bug

Order: Hemiptera

Family: Coreidae

Genus and species: Anasa tristis (De Geer)

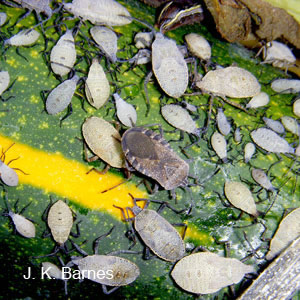

Arkansas gardeners often notice that their zucchini plants dramatically wilt, die, and turn brown and crisp in midsummer. This syndrome is caused by squash bugs. The bugs can be found by closely inspecting the undersides of the leaves or the soil surface under the plants. However, they are wary and shy away when approached. Adult squash bugs are about 5/8 inch long. They are dark brown with lighter brown speckles on the visible portions of the thorax and on the wing bases. The prothoracic margin is light brown, and the edges of the abdomen, which protrude beyond the wings, bear transverse, light brown or orange stripes. Nymphs are smaller and light gray initially, turning darker in later instars. Eggs are elliptical and dark reddish brown. This species occurs in southern Canada and throughout the United States and Central America. It is a particularly severe pest in the American Midwest.

Squash bugs attack nearly all cucurbits, such as pumpkin, squash, watermelon, cucumber, and muskmelon, but they have a distinct preference for pumpkin and squash as egg-laying sites. These plants support high reproduction and survival. However, even among these there may be great variation among species and cultivars with respect to susceptibility. The bugs feed primarily on foliage, but also on fruit. Adults and nymphs pierce the plant with their sharp feeding stylets and inject highly toxic saliva. At first, the feeding causes yellow spots to appear on the foliage. Eventually, the foliage wilts and dies. Sometimes only a portion of a plant wilts, while other portions of the plant and nearby plants remain healthy. The amount of damage is proportional to the number of squash bugs feeding. The bugs also vector the bacteria that cause cucurbit yellow vine disease. The bugs are not usually considered severe pests in well managed, large-scale operations that lack appropriate wintering sites and have the ability to dilute the bugs’ effects because of vast acreage. However, in home gardens and small market gardens they can be devastating. Fortunately for the home gardener, a good crop of summer squash can usually be secured before plants become severely damaged and stop producing.

Unmated adults winter under plant debris or other shelter. They fly into gardens and mate typically in May or early June while host plants are growing. The complete life cycle requires about two months. Eggs are usually laid on undersides of leaves where they are usually found in clusters of about 20 to 40 in angles formed by the meeting of two veins, with each egg arranged about the same distance from the other. Eggs may be produced through midsummer. There are 5 nymphal instars, often with all instars occurring gregariously with adults throughout the summer. Feeding continues until frost, at which time any remaining nymphs die and unmated adults move to winter shelter. There is at least one generation per year. Adults emerging from the first generation may produce a partial second generation before reproductive diapause sets in.

Unfortunately, squash bugs can be very difficult to control. Good cultural practices are the first line of defense. Plants should be maintained in high vigor with proper fertilization and watering. It is important to remove crop debris as soon as possible to eliminate reproduction and overwintering sites. Use of resistant squash varieties, such as Butternut, Royal Acorn, and Sweet Cheese, Green-striped Cushaw, Pink Banana, and Black Zucchini helps to reduce bug problems. Handpicking and destroying bugs and their egg masses and trapping bugs under small boards placed under or near the vines and then destroying them are two popular control techniques, but they must be practiced with vigilance. The bugs can be destroyed by squashing them or drowning them in a container of soapy water. Egg masses should be crushed or burned. Some organic gardeners suggest interplanting with tansy, catnip, marigolds, bee balm, mint, and nasturtiums. Others suggest spraying with a kaolin clay crop protectant, but the effectiveness of such a treatment is not fully established. Some insecticides are available for use in commercial operations by licensed operators. Insecticides available to home gardeners are for the most part ineffective.