Veteran Homelessness Prominent in Fayetteville, NWA

By Erin McGuinness and Leah Nelson

The Razorback Reporter

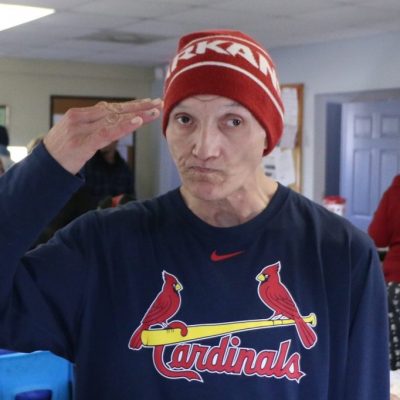

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – Seated in the middle of a crowded room, David King, a homeless Army veteran, belted out lyrics to a gospel song.

“Oh God, you’re not done with me yet,” he sang from the song “Redeemed” by Big Daddy Weave. “I am redeemed. You set me free.”

Between their bites of hot dogs and chocolate chip cookies, other homeless patrons at the Seven Hills (or 7hills) Day Center in Fayetteville shouted at him to be quiet, but King continued.

Homeless Army veteran David King poses after his lunch at the Seven Hills Day Center on Nov. 15. King eats most of his meals and picks up fresh clothing at the center. Photo by Erin McGuinness

“So, I’ll shake off these heavy chains,” he croaked in his raspy voice, passionately waving his arms and patting his chest. “Wipe away every stain, now I’m not who I used to be.”

King, 54, has seen many changes in his life. He moved to Springdale in 2013 to live with his brother, who had recently been released from prison. His brother was arrested for drug dealing and drug use and King was evicted, he said. He moved into a wooded area of Fayetteville for a year. King has been on disability since 2001 for issues with his spine, which has six bulging discs and is shifting, he said.

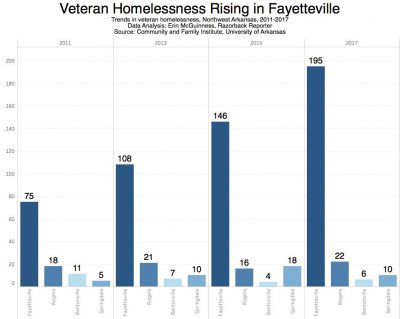

He is one of at least 195 homeless veterans in Fayetteville in 2017, where the number of homeless vets has grown from 146 in 2015, according to data provided by the Community and Family Institute at the University of Arkansas.

In 2009, the Department of Veterans Affairs announced a plan to end homelessness among veterans by 2015. They missed the goal to reach “functional zero,” or the point when there are more housing units than the number of homeless. The national number of homeless veterans dropped consistently until 2016, when the number of homeless veterans increased by 585 to more than 40,000, according to data collected by the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The number also has grown in northwest Arkansas to at least 233 in 2017, according to Kevin Fitzpatrick, director of the Community and Family Institute, which does a local count of the homeless population every other year.

The reasons so many veterans have congregated in the Fayetteville area include the local Veterans Health Care Systems of the Ozarks hospital and a strong local network of city and community support.

Fayetteville is the only local government that has a program in place that helps house the homeless, including homeless veterans, said Yolanda Fields, the city’s director of Community Development.

“I think the city of Fayetteville is doing the ultimate that can be done by providing the housing and providing case management,” Fields said. “We’re doing a lot.”

Fayetteville’s Hearth program provides transitional housing and permanent supportive housing for the homeless. Other programs, such as free busing and the Ranger’s Pantry Pet Food Bank, are aimed to help low-income individuals in Fayetteville.

“We just have a variety of programs that are assisting individuals who are low to moderate income that could become homeless, so we’re trying to divert that possibility,” she said.

Until this year, Fayetteville worked with two federal departments to find housing for veterans:

- Housing and Urban Development/Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD/VASH), which is overseen by both HUD and the VA.

- Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSFV) though the VA.

In early December, the VA announced plans to slash the $460 million budget for HUD/VASH and distribute the money to VA hospitals under the promise that the hospitals would work to help the homeless. The VA secretary backed away from the proposal and the HUD/VASH program will continue until at least 2019, when local VA leaders will report on how and where to allocate the funding.

The joint HUD and VA program housing vouchers, overseen locally through the Fayetteville Housing Authority, lets qualified veterans apply for vouchers. Once approved, veterans have 120 days to find housing. While the program can cover the entire housing cost, veterans are expected to work if they can to help pay rent. Veterans can stay in the program indefinitely, unless they are evicted or exceed maximum income requirements. The program aims to help homeless or low-income veterans get back on their feet and eventually support themselves.

The Fayetteville Housing Authority has 125 vouchers to house veterans and their families, said Joy Hunnicutt, Section 8 housing specialist for the authority.

Army veteran Lance Barnes, 58, uses the HUD/VASH program to help pay for his one-bedroom apartment in Fayetteville after he lived in his car for about a year.

Army veteran Lance Barnes, 58, uses the HUD/VASH program to help pay for his one-bedroom apartment in Fayetteville after he lived in his car for about a year.

A former carpenter, Barnes could no longer work after developing arthritis. He worked at various jobs for weeks at a time until his hands did not function. He knew his hands would not last but needed money and worked for as long as he could, he said.

“I wound up having surgery on my left arm, and then I had surgery on my right arm and all the while my hands were steadily getting worse,” Barnes said. “A carpenter whose hands don’t work is useless.”

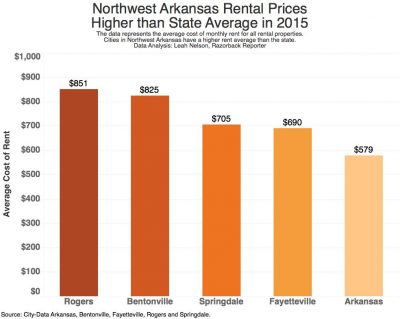

Being accepted into the HUD/VASH program was not a challenge, but being on the waitlist, finding a place to live and dealing with landlords is difficult, Barnes said.

Barnes’ experience finding a home is not unusual, said Deniece Smiley, executive director of the Fayetteville Housing Authority.

Some landlords do not want to rent to veterans in the federal program because they have had difficulty with them, such as psychological issues, police conflicts and renters moving additional people into their apartments, she said.

Sweetser Properties, based in Fayetteville, has rented to HUD/VASH recipients in the past but no longer does, said Bert Morris, the Sweetser Properties receptionist and property manager. The company originally had a 28-unit building that they used specifically for renting to veterans at a lower rate.

“The building that we had veterans in, (there were) constant problems with drugs, alcohol, fighting, breaking windows,” Morris said. “They are not good tenants. They do not take care of the property. They tend to be more drug people or drinking and they’re lots and lots of problems and they do not obey rules.”

Perkins hopes landlords will become more understanding for veterans and look past their non-violent crimes such as sleeping or drinking in public areas, she said.

“Landlords don’t understand what’s happened to a veteran,” Perkins said.

The second federal program that Fayetteville works with is the Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF). It is a rapid rehousing program that has been overseen through Seven Hills Homeless Center for four years.

The VA cut SSVF funding for Arkansas by 33 percent for 2018 and opted not to renew Seven Hills for the program, said Katherine Krueger, director of veterans services for Seven Hills. In 2017, the program served homeless veterans in Washington, Benton and Madison counties on a grant of $714,910. The grant ended Sept. 30. The only Arkansas SSVF program left is St. Francis House Ministries, based in Little Rock, which will now serve 14 counties in Arkansas. For 2018, St. Francis House has been granted $908,775.

“Due to this consolidation and loss of overall funding, St. Francis House will be able to serve just under half the clients Seven Hills has served in previous years,” Krueger said.

An anonymous donor gave Seven Hills a grant that will cover the cut for six months, Krueger said. The organization is using the money to create a stand-alone Veteran Services Program to replicate the federal program on a local level. Seven Hills plans to prove the need for the program in northwest Arkansas and reapply for funding next year, she said.

The funding already is affecting local vets.

King, who eats most of his meals at the Seven Hills Day Center, is rejoining SSVF for the second time after being kicked out for letting another couple live with him. His second stint with the program will be overseen by St. Francis House, but he can stay in the region.

He had a good first experience with SSVF because the employees at Seven Hills genuinely want to help the people they are serving, he said. They offer classes on finances to help the homeless learn to manage money and have classes to help support them emotionally and physically.

“[My caseworker] went door-to-door with me trying to find an apartment,” King said. “He cleared his whole schedule to help me.”

Krueger hopes that the donation will help Seven Hills track a need for supportive services in northwest Arkansas. Since Seven Hills is no longer receiving federal funding for this program, the community has an opportunity to step up, she said.

“We have partnered well with HUD/VASH, so we’ve been really fortunate to have a good working relationship with them to where we’ve been able to access people (homeless veterans) pretty quickly and get them into programs,” Krueger said. “There are still, if you look at our Point-in-Time numbers, so many unsheltered people who it’s just hard to identify them.”

The Point-in-Time numbers refer to the count conducted by UA professor Fitzpatrick, who maps the number of homeless individuals. If an area with a growing homeless veteran population begins losing funding used to help reduce the issue, progress might be slowed down, he said.

“I think that we (Fayetteville) do a pretty good job. We’ve got a pretty good, active VA homeless program. We’ve got a good VA hospital,” he said. “I think there’s a lot of good things that are happening, I just don’t know what’s going to happen if the support goes away.”

One option to help boost Fayetteville’s chances to regain federal funding may lie with a new database under construction.

The Center for Collaborative Care, a NWA-based organization that aims to connect community members to services, is working on a database called Hark. While Hark will serve more than one purpose, organizers are planning to create a list of every homeless person in the area. Once Hark is ready to accept information, homeless service providers will add details about each person that seeks help from agencies such as Seven Hills, the Fayetteville Housing Authority or others.

The Center for Collaborative Care, a NWA-based organization that aims to connect community members to services, is working on a database called Hark. While Hark will serve more than one purpose, organizers are planning to create a list of every homeless person in the area. Once Hark is ready to accept information, homeless service providers will add details about each person that seeks help from agencies such as Seven Hills, the Fayetteville Housing Authority or others.

Once the city has a full list of homeless residents, it can secure enough housing units to assist each of them.

“To reach functional zero, which is the goal, is having enough units to house the average number of folks that would be homeless, in this case veterans, in a given month,” Fields said. “So if you have the units, and possibly the more units than the average veteran homeless (population size) in a month, then you have reached functional zero.”

Krueger thinks that veterans are a good platform to begin the process to reaching functional zero, she said.

“Homelessness has a lot of stigma around it, so I think raising awareness is huge,” she said. “The national goals are to use veterans as a pilot for reaching functional zero, and then from that subpopulation going to those experiencing chronic homelessness, and then the rest of the general population as experiencing homelessness.”

Despite his struggles to find permanent housing, King is convinced things will improve for him and he uses music to push through his difficulties, he said.

“Oh God, you’re not done with me yet,” he sang.

The music keeps his memory and faith sharp, he said, adding that if he doesn’t forget the song lyrics, he will not forget his life.