VA Hospitals Battle National Nursing Shortage

By Katie Serrano and Betsy Davis

The Razorback Reporter

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – The largest health care provider in the United States, serving more than 9 million individuals each year, is struggling to keep nurses on staff amid a national shortage.

The demand for Veterans Affairs services has been increasing, and losses among the agency’s health care providers also have been increasing, according to a 2016 Government Accountability Office report.

Six years ago, 5,897 VA employees left the system; that number grew to 7,734 in 2015. Physicians, registered nurses, physician assistants, psychologists and physical therapists were among those who left.

Nationwide, the VA has around a 10 percent vacancy in nurses and employs 68,000 nurses total, said Bruce Appel, the nursing union’s vice president.

More than 1 million registered nurse openings will occur by 2024, according to The Bureau of Labor Statistics. There are about 3 million nurses in America.

Nurses are one of the most critically needed positions at VA hospitals across the country, according to the inspector general’s office. The VA hired 8,528 nurses in the year 2015 but lost 4,966 that same year, according to the same report.

“The undersecretary of the VA says that we are short 49,000 positions VA-wide, but in reality that number is much higher,” Appel said.

One of the first known nursing shortages in the United States began in the mid-1930s following the Great Depression. The shortage grew critical and attracted congressional action in the 1960s. Despite that intervention, a nursing shortage continues today.

Initially military nurses – particularly during World War II – fueled the nursing shortage. The military had more than 77,000 nurses serving during World War II. That cut the civilian nurse population by about 25 percent, according to a report by the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

After World War II the shortage continued. Lower enrollment numbers in nursing programs around the country exacerbated the shortage. Enrollment in the U.S. dropped by about 23 percent from 1946 to 1949, according to American Nursing: From Hospitals to Health Systems, documentation from the University of Pennsylvania.

The U.S. government responded with the Nurse Training Act of 1964. That gave $283 million to building nursing schools, expanding programs, reimbursing of some educational costs, establishing a low-interest student loan program and supporting the Nurse Traineeship Program. Nurses seeking a master’s or doctoral degree could receive up to 36 months of training to be teachers, administrators, nurse practitioners and other areas that require advanced training.

The act that President Lyndon B. Johnson signed had positive effects, but it did not permanently resolve the nursing shortages.

Two of the main contributors to the nursing shortages dating from the 1970s have to do with increased chronic illnesses and an aging population, primarily baby boomers, according to Nurses for a Healthier Tomorrow. The generation, whose age ranges from 53 to 71, is experiencing a surge in chronic illnesses; they need more care, causing an increase in demand for nurses and other medical staff.

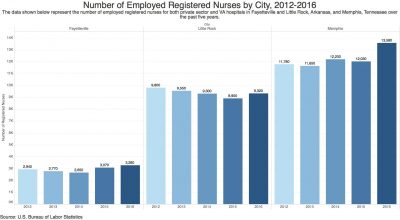

VA hospitals in Memphis and Little Rock are seeing this shortage firsthand. In Memphis, nurses continue to raise concerns about nurse-to-patient ratios.

“I feel as though the overall nurse-to-patient ratio is overwhelming to the nurses and I often listen to feedback from other nurses on how much of a struggle the patient load is,” said Susan Ferguson, a cardiac nurse at the Memphis VA hospital. “The patient load is overwhelming so the nurses are limited to the attention they can give toward the patient’s needs.”

As the baby-boomer generation grows older, private sector hospitals also have experienced nurse shortages nationwide, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Other matters related to the shortage include the fact that nursing schools across the country are struggling to expand capacity to meet the rising demand for care in the midst of national healthcare reform.

Some University of Arkansas nursing students will join the workforce after graduating in 2018, facing this shortage head-on.

“I never had a rotation at the VA, but I know people that have. I’ve gotten pretty lucky in that I haven’t. Not that I don’t appreciate what the veterans have done for us, but just from what I’ve heard, I don’t think it would be a good fit for me,” said Grace McKinney, a UA senior in nursing. “I personally wouldn’t ever consider working for any VA, just because I haven’t heard good things about any of them.”

The U.S. is projected to have a nursing shortage until at least 2030, according to the United States Registered Nurse Workforce Report Card and Shortage Forecast, published in 2012, the last data reported.

The GAO found that 28 percent of VA nurses’ loss was linked to issues involving advancement in the workplace and 21 percent was linked to work dissatisfaction, including unfavorable nurse-to-patient ratios and long hours.

“Every day nurses are talking about leaving, and they are leaving,” Ferguson said. “They are exhausted from the poor morale from management and being required to work a patient overload. Nurses know they can go elsewhere, make as much money, and have a benefit package while caring for fewer patients under better management.”

In June 2017, the Little Rock VA was short 140 full-time nurses. That is partly responsible for patients’ longer wait times and employees’ longer work hours. Hospital workers protested outside of the VA in response to shortages, prompting an investigation from the Department of Veteran Affairs. The Little Rock VA responded by implementing what officials describe as an “aggressive” recruiting program, instituting a referral and stay bonus for experienced RNs and recruiting incentives of up to $15,000.

Rick Cooper, the assistant nurse manager for the emergency department at the Fayetteville VA, said that 20 nurses work in his department; two more are training.

Rick Cooper, the assistant nurse manager for the emergency department at the Fayetteville VA, said that 20 nurses work in his department; two more are training.

“You know, we’re getting there,” Cooper said when asked about there being a shortage within the emergency department. “Before I came here there was kind of a change, a changeover in staff, so there’s been some big changes that have helped.”

The Fayetteville VA is not experiencing nurse shortages, but that wasn’t the case just a year ago.

“Nobody can tell you with a straight face that the Fayetteville VA is suffering any sort of nursing shortages at the moment,” Appel said. “In 2016, however, when the ER nursing staff wasn’t under Nursing Service Management it almost had to shut down because there were not enough people to run it.

“In 2014 and 2015 we had to shut down beds, and we shut them down because we simply couldn’t staff them. We lost about 60 nursing positions. We were ready to take to the streets last winter, but after filing our grievances the ER hired the staff they needed to run the department. It was in critical condition, putting patients and nursing license at risk,” Appel said. “And it was all about saving money.”

Cooper attributes the current temporary lag in the number of nurses to the VA’s extensive and lengthy hiring process.

“I think with any government position there’s always going to be these background checks and whatnot, so with that being the process, it just makes it tough to get people here,” Cooper said. “We get them here, it just takes a while.”

Michael Boney, a Fayetteville VA staff RN, said that if Fayetteville has experienced any sort of lag in turnover, it is because of the hiring process.

“One reason for staffing issues at VA facilities is when there is turnover, it takes a very long time to replace that nurse or other healthcare provider,” Boney said. “First, the position must be approved to be advertised and filled. Then there is an advertisement period for the position, usually two to four weeks. Then the interview period and a complicated vetting process prior to starting.

“Both times I have been hired at the VA it took three to four months from the time of application to start date. After starting, there is a two-week new hire orientation period prior to starting on the unit. So, when there is turnover, it takes a nurse out of rotation for several months,” Boney said.

Jason Matkowski, a medical service assistant at the Fayetteville VA hospital, works on his computer Nov. 15. Photo by Chase Reavis

The VA has offered incentives such as scholarships to attract nurses and other employees to hospitals.

“We acknowledge that employees want to advance their education,” said Raquel Alvarado, Associate Chief Nurse of Acute Care Services at the Fayetteville VA. “We can offer scholarships so nurses can go to school and change their associate degree to a bachelor’s, master’s or doctorate. If they give us their time, we will pay them back for it.”

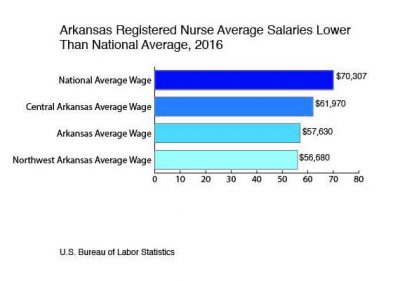

Registered nurses with an associate or bachelor’s degree typically make between $65,000 and $70,000, according to a registered nurse pay scale from 2017 provided by Appel.

On a national private sector scale, Arkansas RNs make an average of $57,630, in comparison to California, which has the highest average RN salary at $101,750.

A 2013 Future of Nursing Report called for increasing the number of baccalaureate-prepared nurses in the workforce to 80 percent and doubling the population of nurses who have doctoral degrees. The nursing workforce falls short of these recommendations with only 55 percent of registered nurses prepared at the baccalaureate or graduate degree level.

“The department managers are not always Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree nurses, they may have had no leadership or management experience, yet are running an extremely busy department that seems to have no control over it,” Ferguson said about Memphis.