This post is part 2 of a 2-part series about chicken. Read Part 1: “Chicken: The Universal Bird of the Modern World”

Chicken. It is the most popular meat in the world, with people from every corner of the globe enjoying it regularly.

In a previous post I traced the history of this domestic bird and showed how the chicken went from a fighting bird of jungles of Southeast Asia to the favorite addition to the deep-fryers of Kentucky.

In a previous post I traced the history of this domestic bird and showed how the chicken went from a fighting bird of jungles of Southeast Asia to the favorite addition to the deep-fryers of Kentucky.

Today, commercially available chicken meat comes in one of two versions: forage fed on pasture farms or mass produced by giant, vertically integrated, chicken industries.

Since this is a sustainability blog, you’re probably expecting me to immediately denounce the massive chicken industries as evil and extol the wonders of the pasture farm, but the truth is both forms of chicken production have their sustainability wins and woes. In this article I have attempted to fairly examine the important differences between to two paths to producing chicken, comparing the pros and cons of each.

This article only deals with the production of broilers—chickens bred for their meat. A later article will look specifically at the chicken egg market. It must also be noted what exactly I am talking about when I refer to “Industrial” or “Pasture” Farms. For the purpose of this article, Industrial Farming can be defined as a vertically integrated entity that produces chickens from embryo to broiler in a self-contained environment. About 95% of all broiler meat is produced this way. For this article, I use the term Pasture Farming to refer to non-vertically integrated farms that raise chicks to chickens on a foraged diet.

To be clear, chicken marketed as “Free-Range,” “Pasture Raised,” or even “Organic” are not necessarily raised on a foraged diet or outdoors.

In fact, most of the such labeled chicken still comes from industrial farming entities. Often, the only difference between a normal chicken farm and a “free-range” chicken farm is a small gravel enclosure attached to the chicken house by a 2ft x 2ft door. As I’ve written before, food labels are commonly deceiving, so if you want to be sure you know what you are buying, look up the practices of the producer before you purchase. You might just end up realizing the product is not what it led you to believe.

Industrial vs Pasture Farms

What’s in a Bird?: differences in the breed

The industrial farm has spent the past 60 years perfecting their broiler breed. As mentioned in the article on chicken history, the metamorphosis of the for-meat chicken of 1957 to the broiler of today is astounding.

A few of the many chicken varieties of the world

The modern broiler can convert feed into meat at an alarmingly efficient rate, needing only 1.87 lbs of feed for every 1lb of weight, and reaching a market weight of 6.24 lbs in just 48 days. This is an improvement of over 100% from the 1950s averages. This same breed of bird, named the Commercial Cornish, is the universal breed of industrial chicken farms.

Pasture farms may specialize in one breed of chicken, or may raise several. Different chicken breeds have different characteristics, making them suited to different environments or purposes. The Cornish Cross, a hybrid of the Commercial Cornish breed used in industrial farms, is widely considered to be the best foraging broiler available. This is because the bird retains some of the idealized metabolism of the Commercial Cornish, while its crossed genes makes it more suited for a foraged diet. The Delaware and Java are also popular for-meat birds, and are often preferred by pasture farmers for their “pure breed” status, although that they more feed per pound of meat than their Cornish cousins. Still different breeds will be used on a pasture farm that wants a bird to produce both eggs and meat.

Production Practices: differences in facilities and feed

The most obvious difference between an industrial chicken farm and a pasture raised farm is the sheer size of the operation. Industrial broiler farms can have 25,000–90,000 birds per farm, while the largest pasture farming operations average 14,500 birds annually with the more common, smaller farms peaking at around 4,000 birds per farm.

Another major difference between industrial farms and pasture farms is in the feed the birds are provided. Industrial farms have put as much work into perfecting a homogeneous, idealized feed as they have in producing a homogeneous, idealized breed. The feed is grain based and calorie dense, intended to provide the necessary nutrition to grow the bird into a meaty broiler as quickly as possible. According to the National Chicken Council, “Chicken feed consists primarily of corn and soybean meal with the addition of essential vitamins and minerals. No hormones or steroids are allowed in raising chickens.” Pasture farms feed their chickens similar feed, but they also allow their birds to forage, which is believed to add essential vitamins, minerals, and nutrients to the birds diet.

Despite this, there is no scientific evidence to show any significant difference between the nutritional value of industrial and pasture raised chicken meat.

Industrial farms also differ from pasture farms in that they are “vertically integrated.” In common language this means that every part of the chicken production line—from the feed mill to the hatcheries to the processing plant—are all owned and/or operated by a single company and their affiliates. As such, the company owns the layers and the chicks and the feed that eventually become the chicken product they sell. Conversely, an independent pasture farm will need to buy their chicks and feed from outside sources, and will often sell the mature broilers to a processor to be sold to consumers.

Sustainability

Now comes the big issue. We’ve looked at the difference between industrial and pasture farms when it comes to practices, breeds, and nutrition, but what about their overall sustainability? Which method is better when it comes to creating a better world?

The truth is that the answer isn’t black and white. There are thousands of factors that affect the sustainability of chicken production, most of which I don’t have the space or expertise to delve into here. There are, however, two basic issues that are important for everyone to consider—the environmental impact, and the product output.

You may have heard of some of the environmental concerns linked with the poultry industry. Large industrial farms use large amounts of energy and water. The production of feed for the birds requires its own water and energy inputs, as does the processing of the carcasses, the packaging, and transportation of birds and product. Raising hundreds of thousands of chickens also results in hundreds of thousands of pounds of chicken litter—aka chicken poop. While this litter is know as a great fertilizer and is often used as such, mismanagement of chicken waste can and has led to major environmental and health impacts in surrounding areas. Industrial chicken farms will be the first to point out that their massive structure and specialized systems are designed in a way that minimizes the environmental impact per bird—lower even than your average pasture farm. After all, needing less space/feed/water/energy/time to produce each pound of meat means less of an environmental impact as well, right? This this may be true, but when you multiply that impact-per-bird (however small) by the 9 billion broilers produced in industrial farms last year—the impact of the poultry industry as a whole on our planet, while less than that of pork or beef, remains staggering.

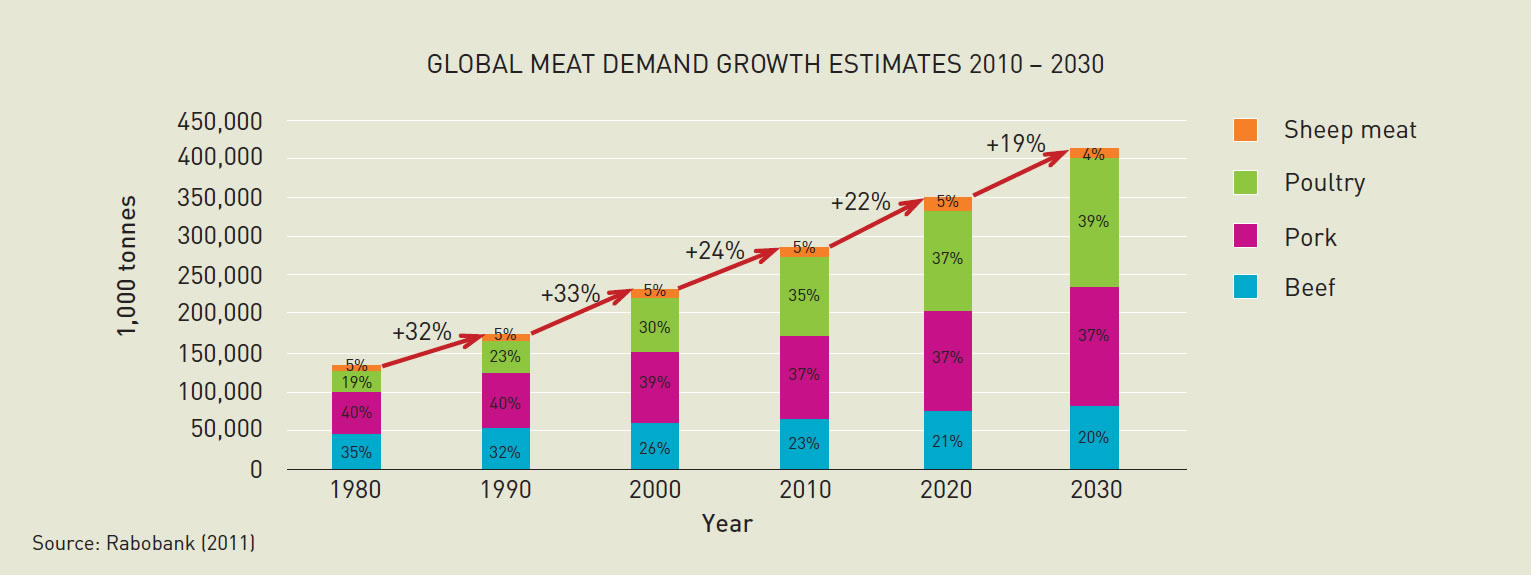

This brings me to my second point. In my research into the chicken industry, I came to an unexpected conclusion. I was expecting to find that the key to sustainability in the world of poultry was in a change in practices or better management of energy inputs—something that aligned with the old sustainability adage of “doing more with less.” But as I truly began to think about the statistics of global chicken production and consumption, I was struck with a new realization. You see, the industrialized chicken farm has made chicken available to the world, by decreasing the cost of production. According to the Cornucopia Institute, “the price of chicken has dropped dramatically over the past few decades, becoming the cheapest meat available in the US. As a result, consumption has doubled since 1970.” Advancements in technology have made meat cheaper to produce, and as much of the world has developed and more of the global population has entered the middle class, the demand for meat products has increased. Combined with a growing global population, and our total consumption of meat continues to climb every year.

world egg

As mentioned above, no matter how low an environmental impact per chicken we achieve, as long as we are still producing billions of chickens per year, the effect on our overall sustainability will remain far from negligible. The key to sustainability in the poultry industry, then, may actually not be in the production of chicken, but in their consumption. We have grown used to having abundant and cheap chicken, and cheap meat in general, and much of the world is quickly becoming accustomed to the same. It seems to me, though, that if we truly are committed to sustainability, it may be necessary to change the old adage of “doing more with less” to simply “doing with less.”