Mishell Quintero moves a cash register at J.C. Penney. Photo: Stefany Lemus

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – While a number of Northwest Arkansas workers struggle with money, Mishell Quintero has a more complex challenge: navigating the workforce as an undocumented immigrant.

Quintero, 23, works two jobs to help her five-person family make ends meet. At J.C. Penney, she works as a cash room clerk four days a week, which involves sorting and depositing the retailer’s money and fixing cash registers. She also works as a private caregiver for a paraplegic individual in the area.

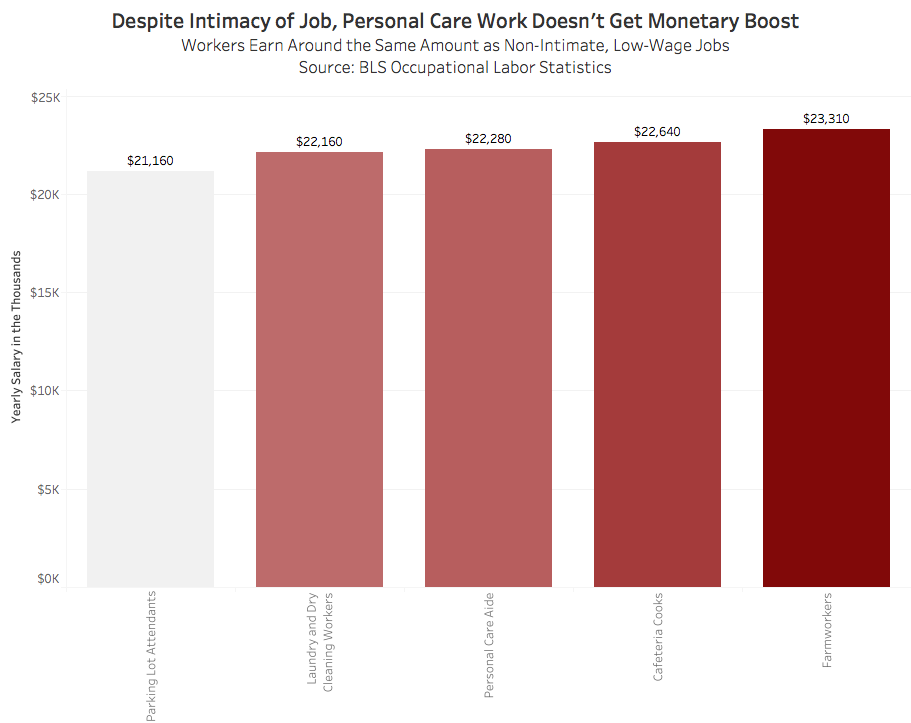

In Quintero’s role as a caregiver, she helps her employer with getting dressed and showering. Despite the intimacy involved, the salary of such a worker doesn’t move past the same lower wages for menial and less intimate work.

Finding work as an undocumented immigrant

Quintero was seven years old when she and her younger sister came to the United States, hiding in the back seat of her uncle’s car. He used fake papers to gain entry. Quintero’s mother had entered the country illegally through Arizona. Her parents had extended family in Springdale, so they family moved to the area and have remained here since.

Quintero said it wasn’t until she became an adult did the magnitude of her immigration status become apparent. After turning 18, she began searching for jobs to help support her family. That’s when reality hit: she wasn’t a legal resident of the country.

“My parents didn’t lie to me. They didn’t say that I did have papers here, but they never told me that I didn’t have papers,” Quintero said. “I was never worried about having to have a job until I was 18 or never having to drive until I was 18 because they were always like, ‘You’re not going to do anything until you turn 18.'”

Quintero would be covered under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, known as DACA, which defers deportation proceedings for two years for children brought to the United States illegally. The Trump administration is seeking to end the program and its outcome is pending several legal challenges. She applied for and was granted a work permit, but she said she was scared of what employers might think.

There are times when the family gets so tied up in paying bills that they eat at food pantries and soup kitchens. In the end, Quintero wants to attain citizenship so she can get a higher-paying job and eventually live her version of the American dream.