Approximately one-in-three residents of Fayetteville fall below the poverty line. Alejandro Zeballos and Abigail Jobst were among those who struggled with that fate.

Jobst, 24, originally from St. Louis, waited tables at Grubs Uptown for most of college. Even though she no longer works there, the experience showed her what poverty was like. As a journalism student at the University of Arkansas, it was easy to balance school and work. She had to support herself after her parents stopped giving her the little they did. In 2015, Jobst met Zeballos, and they married in December of 2016. In the summer of 2017, Zeballos, an immigrant from Bolivia, lost his education visa, forcing him to lose his job at a marketing firm.

For close to six months, the married couple lived off of a servers salary alone. Being a server is inconsistent at best – especially at this location. Some nights, Jobst would leave with $350 in cash, and some nights she would leave with $19.

“I had to balance giving up things I love,” Jobst said.

Beyond the financial instability that comes with being a server, there was emotional instability as well.

Most graduates expect to get a job immediately after graduation. The majority of Jobst friends achieved jobs with salaries in the five-figures soon after leaving college, and she didn’t. This left her feeling unaccomplished and emotionally behind. Jobst did not get a job until almost a year and a half after graduation. Recently, Jobst accepted a position with the Girl Scouts of America where she is a recruitment supervisor.

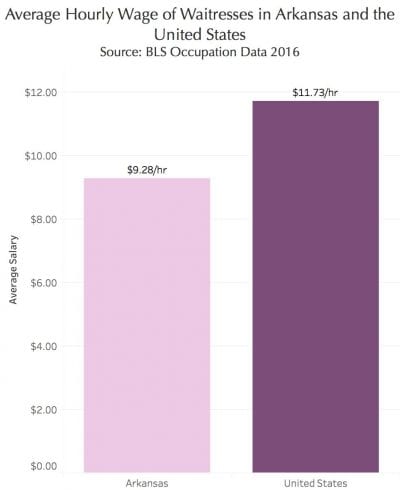

For most college students and recent graduates, a job like serving is very common. The hourly wage for servers in Arkansas is lower than that in the United States as a whole. When this is the primary salary, that person immediately falls below the standard of living.

Luckily for Jobst, Zeballos had a job that brought in nearly $50,000 each year. But when his immigration paperwork failed to go through, Zeballos lost his visa, and as a result lost his job. Jobst speaks on the immediate shock of the loss, and what they had done to prepare.

Luckily for Jobst, Zeballos had a job that brought in nearly $50,000 each year. But when his immigration paperwork failed to go through, Zeballos lost his visa, and as a result lost his job. Jobst speaks on the immediate shock of the loss, and what they had done to prepare.

When the couple married in 2016, they knew that the deadline was coming soon to extend the work visa. They blame their predicament on how late the documents were submitted. They spent what money they had left to pay for an immigration lawyer and print documents. They spent hours making sure everything was accurate, and “printed, labeled, and put together”, Jobst said.

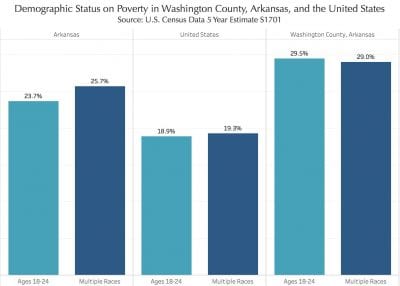

Seven months passed before any kind of court date, until late October 2017. Zeballos gained his green card back, and went back to work almost immediately at the marketing firm. Jobst and Zeballos were not alone in their poverty status In Washington County, Arkansas, nearly 30 percent of residents aged 18-34 remained under the poverty level. For multi-ethnicity households, that percentage is 29%.Jobst and Zeballos met both of these criteria while living on a servers salary.

During their time below the poverty line, Jobst and Zeballos were among the statistic of multiple ethnicity households that were in poverty. The struggles of being newlyweds and living under the poverty line bring on a set of struggles.

Not only are the struggles financial, but they are also emotional. Their relationship took a toll because of the many negative factors that come with being unemployed and poor.

“That was the least close we had been,” Jobst said.

The security of having a job, a steady income, and financial stability are not only meaningful for young couples, but also necessary.