Agenda for Monday, Oct. 8

–Context!

–Common Errors

Context #1

Add the Quick Facts for city population, demographics.

Little Rock: African American comprise 42 percent of Little Rock’s population. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/littlerockcityarkansas,US/PST045217

Add typical salary from Occupational Employment Statistics database for Arkansas

https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_ar.htm

Common Errors – Math

Percent vs Percentage Point

At Lyon College, 67 percent of non-first-generation students paid back their loans within five years, while only 53 percent of first-generation students did the same, which results in a 14 percent POINT difference. The median debt for both types of students was the same though, at $12,000.

You mean “percentage point.” 14 percent of 67 is 9.4.

Steve Doig – MathCrib-Doig

Common Errors – AP Style on Numbers

AP Style on Numerals:

Numerals – AP Stylebook-2avrxtn

Common Error – Divi Library

Divi Builder. Do Not Save to Library.

Context #2: Build Charts for Context

First row: The overall median debt for Arkansas students; for men, for women.

Second row: The overall median debt for first generation students. And non-first generation

Third row: The overall statewide repayment rate, and the rate for men, for women

Fourth row: The overall median debt for white, black, asian, hispanic

Post on WordPress with the category Context

Research – Data Question

The Financial Aid department does not report loan repayment info to the Department of Education. “Once the students leave us we don’t track their information anymore,” he said.

Question: Look at data dictionary for source of this information. All 1,826 columns explained here.

https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/assets/FullDataDocumentation.pdf

https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/assets/CollegeScorecardDataDictionary.xlsx

Homework

#1: Read this report and compare to your work on context. Prepare to discuss it Wednesday

https://ticas.org/sites/default/files/pub_files/classof2016.pdf

#2: By 11:59 p.m. Tuesday, fix the issues with your charts and stories from Assignment #2. Post on WordPress, use the Context category for a tag

Assignment 4/25

Additional Graphics- Ann Claire Johnson REVISED

Additional Graphics-Aubry Tucker

Class 13, April 19

I’m With Her

Agenda

- WordPress Team

- 6 p.m.: Bobby Ampezzan

- Best Overview Essay

- Fix stories, build page

WordPress Team

Nicole Plumlee

Jared

–Mock Up Designs

We’re working with this idea of three sliders:

–Mobile device – editing in Divi

–New single page site. Editor role

–Build!

Fact Check

Attached is a spreadsheet for the fact checking process. Please put the name, email and phone number of the people you spoke to on this list. I will be contacting them and sending a few quotes to make sure everything is ok. I do this on major projects and rarely have any issues – the people we interview really appreciate the follow-up.

Editing Punch List

Aubry Tucker

-Update Sherrod Bryan story with his restaurant closing.

Mary Kerr Winters

Modify this to make it just an interactive Tableau map that we will use in the gallery.

–bring in the audio files, fix audio for Cathy Lee

Andrew Epperson

Esmeralda Jaimes – fix edits, photo. rewrite

Philip Sais audio.

–Question for Epperson on the Sais graphic – bar musicians. where did you find that data?

–re-edit the photo and crop it tighter

Quintero

(brief introduction needed for second clip)

Tonney Gazaway

: https://wordpressua.uark.edu/datareporting/tonney-gazaway-andrew-epperson/

(profanity at 18, 42. edit)

Ann Johnson

Katie Serrano

1) Dana Ralpho. Split this into a separate post.

–Wage she earns at Wendy’s

–Audio clip

–More detail about her situation. This story is very brief and incomplete

2) Renee Smith.

(AUDIO NEEDS EDITING– CHECK SOURCE FILE. HARSH SOUND)

–Fix graphic. Just display average annual wage

3) Davis.

–Who is Quinn Childress?

4) Lara

Clean up edits in red.

Audio needs an introduction

Elisabeth Butler

Jobst

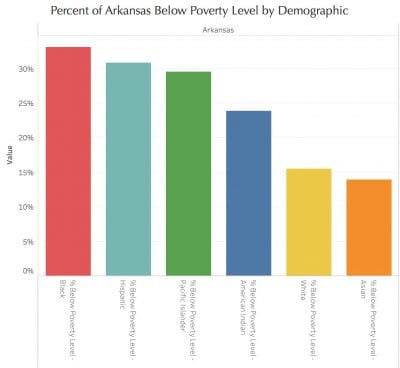

Poverty by Race in Arkansas: Elisabeth Butler

Redo this to focus just on Arkansas

(https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wordpressua.uark.edu/dist/0/367/files/2018/02/Demographics-and-Poverty-1ebo4l8.jpg)

–Abigail Jobst: Not sure where she is working (Grubs?), how much she making and if they remain in poverty status if Zeballos is back to work making $50,000?

All right. I think I’ve looked at all of the profiles and listened to the audio bars available.

Bobby Ampezzan

More Tips from Ampezzan

Homework

- Format and Post Your Stories in a Slider on the New Web Page

2. Fix any items on your punch list. That will include photo editing (Crop and Adjust Brightness) and audio.

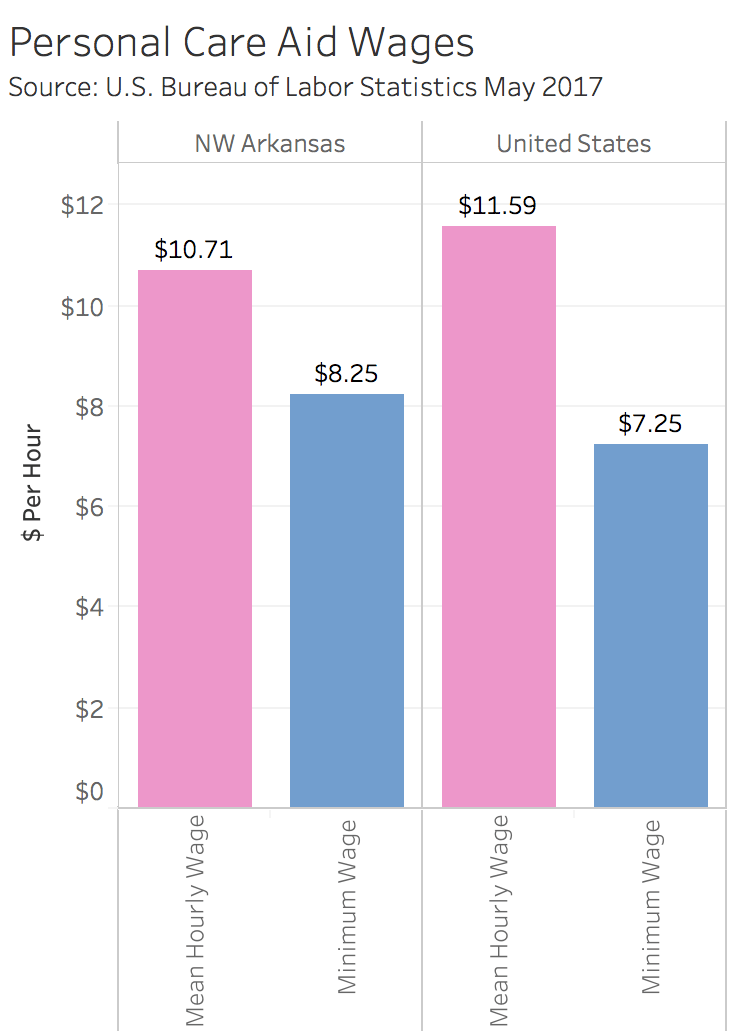

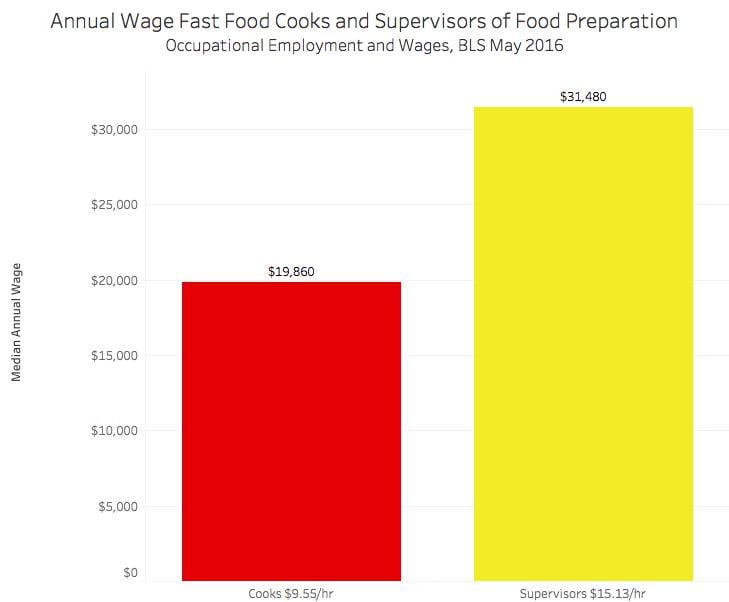

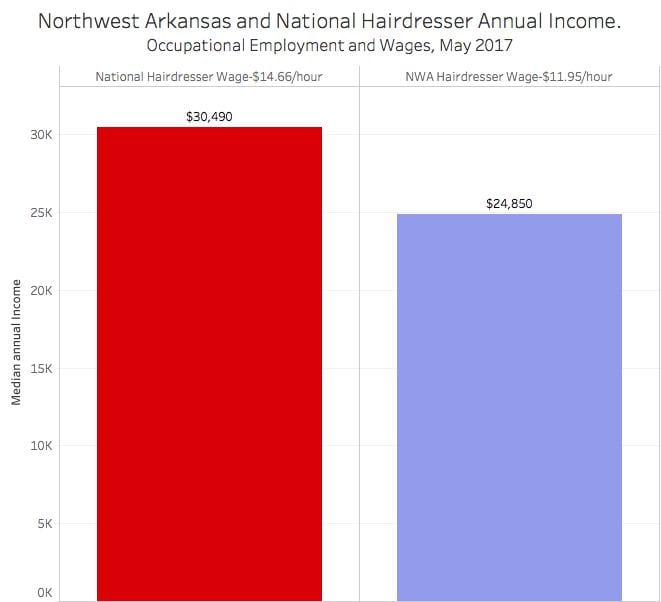

3. Develop the following graphics for the various occupations:

–Fast food manager — Aubry

(edit this: source of data, year. (https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wordpressua.uark.edu/dist/0/367/files/2018/03/FinalCooksSupervisors-276uelm.jpg)

–Waitress – Serrano

–Retail sales — Mary Kerr

–Manager Fast Food — Serrano

–Retail Store clerk — Ann Johnson

–Child care — Elisabeth

–Bar Musician — Andrew

–Barber – Aubry

–Custodian – Andrew

–Personal care assistant – Ann Johnson

Due 11:59 pm Wednesday April 25

Esmeralda Jaimes, Office Cleaner. By Andrew Epperson

Esmeralda Jaimes cleans an office at Channel 5 News in Fayetteville, Arkansas, on April 8. Credit: Andrew Epperson (photo is blurry. better version?)

For one other Northwest Arkansas resident, her main goal is to simply give her four children a comfortable life and continue to live her version of the American dream.(rewrite – this is a bit predictable)

Esmeralda Jaimes, 40, moved to Fayetteville from Mexico in 2001 and worked a variety of jobs before she took a job cleaning the Channel 5 News offices. As a single mother, she cleans a number of offices around Northwest Arkansas and does other side jobs to earn money to support her family.

After Jaimes’ mother died, she needed to get away from Mexico and the memories that depressed her, she said. She and her then-husband moved to America in an effort to give their children a better life, and Fayetteville was a natural choice because several members of his family lived in the area. (how much does she earn? wage?)

The roughest month of the year for Jaimes’ finances is August. This is because she has to buy school supplies, clothes and shoes for her children around that time, she said.

Jaimes is taking English classes to improve her communication in America and give her the opportunity to open up her own cleaning business, she said.

Despite a number of Americans’ negative views concerning immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries, the majority of citizens in Northwest Arkansas have been helpful and supportive of Jaimes as she’s lived in the area, she said.

___________________________________________

Version 2

Esmeralda Jaimes cleans an office at Channel 5 News in Fayetteville, Arkansas, on April 8. Credit: Andrew Epperson

For one Northwest Arkansas resident, her main goal is to live the American dream she sought out when she left Mexico almost two decades ago.

Esmeralda Jaimes, 40, moved to Fayetteville from Mexico in 2001 and worked a variety of jobs before she took a job cleaning the Channel 5 News offices. As a single mother, she cleans a number of offices around Northwest Arkansas and does other side jobs to earn money to support her family.

After Jaimes’ mother died, she needed to get away from Mexico and the memories that depressed her, she said. She and her then-husband moved to America in an effort to give their children a better life, and Fayetteville was a natural choice because several members of his family lived in the area.

Jaimes declined to share her exact salary, but she said there are times when she struggles to come up with all the money needed to support her family. The roughest month of the year for her finances is August. This is because she has to buy school supplies, clothes and shoes for her children around that time, she said.

Jaimes is taking English classes to improve her communication in America and give her the opportunity to open up her own cleaning business, she said.

Despite a number of Americans’ negative views concerning immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries, the majority of citizens in Northwest Arkansas have been helpful and supportive of Jaimes as she’s lived in the area, she said.

Overview Essay – Butler

Throughout the course of this class, my eyes were opened to many things involving those who are in the working poor category. I was able to see the true struggles of those who I personally work with and relate with, and also those who are much worse off and truly struggle. Through my classmates interviews, I was introduced to the positivity that those in that we consider “working poor”. I also developed a new insight to how interviews are held when you don’t know the subject, and when there is sensitive subject matter at hand. I personally find interviews very uncomfortable, but with such a topic on the line it was very influential on my feelings about reporting.

Some of the projects I found most interesting, were those that included the most difficult of situations. I learned about many of these once we went back and looked at the class as a whole and compiling our projects for a major dashboard. Andrew’s story about the piano player, Phillip. Not only did he provide an international face for the project, but also he was someone who did not work in food. I think in general, myself included, have a hard time imagining low wage workers that do not work in the food industry. Like most waiters and waitresses, the piano players at Willy D’s operate on minimum wage and tips. This story also provided an interesting insight on how music isn’t always about pleasing others, it’s about pleasing yourself and making others happy with what you do. Especially in a college town where Dickson Street is the heartbeat of many Saturday nights, having a profile of someone who interacts with students daily adds a whole new face to the bar scene. The other profile that intrigued me was the one with Sherrod. He worked at one location, and then was the victim of a closing restaurant and was moved to another one. I think that facet alone gives a tangible view of how inconsistent being a low wage worker truly is. Aubry Tucker discovered this fact long after the interview with him, and the accidental follow up kept me interested in the story. When dealing with people who are in such situations, it is rare that you run into them again, as many of them bounce around. But for Sherrod, he was around and able to share his story in a unique way to following up – reverse of how it usually works.

When it comes to defining working poor and deciding what to wording to use for this class, there are a lot of social and economic factors to take in. In my opinion, poor is a bit of a strong word. But in most cases, if someone has “x” attribute, they know about it. For example, an African-American person knows and realizes that they are African-American, so there’s no need to skirt around the term. I think this works the same way with Working Poor. They are working for what they have, and often times what they have is not enough, the dictionary definition of poor. I think for the purpose of News Ethics and titling the final project for this course, “poor” should not be used, rather something more along the lines of “low wage workers”, since that is the more political correct term.

Aubry Tucker – Overview Essay

Over the course of this project our team sought out to understand what it means to be working poor, who the working poor are, and if that term properly represents them. We began by researching Arkansas incomes by county, and interpreting the data. The numbers seemed bleak. There were steep rates of single mothers in poverty, especially in comparison to the general community. According the the U.S. Census some races in the Northwest Arkansas area have poverty rates that reach over 50 percent. We also found that the higher the median income for a community the lower the amount of people whose annual income was $25,000 or less. The association with median income, and those with a low annual income made the solution seem to be raising wages. However, there was far more to be uncovered through our in-person interviews with low wage workers in Northwest Arkansas.

When we moved on to interviewing low wage workers, there were a few necessities we needed to keep in mind. Our interviewees must work full time, they must be making something close, or equal to minimum wage, and that we should aim to find a diverse, thought-provoking subject. With the research we had conducted there was intimidation in starting the process, the numbers had made the low wage employees’ situation seem like an unrelenting struggle–in Nickel and Dimed, by Barbara Ehrenreich in which as an embedded reporter, she takes on the role of working poor in Florida for an extended period. Her experiences are very humbling as she pinches pennies, goes hungry, and physically and mentally drains herself to make ends meet. There was pressure to represent the people who were opening up to us about their work and personal life with dignity. One man I interviewed at a barbershop while he was cutting hair and said his number one goal was to be able to leave something to his children. He told me about his closeness with his clients, and pride in his position. One of our reporters, Andrew Epperson was able to interview a woman that had overcome homelessness, and now works to do the same for others at a local homeless resource, 7 Hills. Another reporter, Ann Claire Johnson interviewed a man working as a gas station clerk, while homeless, and pursuing his GED. The commonality in the array of people that we spoke to was their uplifting attitudes. Apprehension became insignificant to the overwhelming air of positivity in the interviews of people matching the requirements we were seeking. These working poor people never offered complaints, they consistently portrayed hope for working to be better, and that accomplishing more was within their grasp.

Something to consider is the definition of working poor, and if that definition is correctly representing the people. We took the experiences of 20 different people that could fall under the category of working poor. If you define working poor as an employed person, making less than or equal to $25,000. At times even when the interviewee met this description, they accounted for luxuries they could afford and time they were able to spend for themselves, or their families. Interviewees often didn’t define themselves as poor, many considered their lifestyles to be middle class. What does working poor mean to you?

Overview Essay – Andrew Epperson

Throughout the semester, the interviews conducted by the students in Advanced Reporting and Data Analysis revealed a varying level of economic insecurity in Northwest Arkansas. Although the faces, roles, and backgrounds were different, there were a number of connecting factors that remained constant across the spectrum.

One evident aspect throughout the majority of those interviewed was that they were positive about their respective situations, and they seemed to be happy about what they had and were optimistic about their futures. In Ann Claire Johnson’s report on Chris Pfaff, a homeless gas station worker, it became evident that even those who live in the most-extreme versions of poverty in Northwest Arkansas seem to have an innate sense of purpose. “I come in every day with my head held high,” Pfaff said, according to the report.

Still, when one thinks of extreme poverty, he or she often is under the impression that a person in that category struggles to meet their basic necessities of life. In the interviews conducted for class, it becomes quite apparent that many of these individuals can afford the things that keep them alive as well as other commodities that indicate some level of spendable income. In one of Mary Kerr Winters’ pieces, Nicholas Pando, a game shop worker and assistant for Lindsey Real Estate, is in a well-enough-off financial situation to where he doesn’t have to pay his own rent. Jenny Ridyard, a former homeless individual who now works at 7Hills Homeless Center, is completely out of poverty and now has the opportunity to buy a house within the next year.

While these interviewed individuals would not fit into the typical thought of extreme poverty, they still struggle with attaining the financial security many people in Northwest Arkansas enjoy. In Katie Serrano’s piece on Wendy’s worker Dana Ralpho, the reader is introduced to a student who might otherwise be able to go to college like many of the people in the area, but she instead has to support her family while attending Fayetteville High. When she graduates, she will join the Navy to earn a better paycheck than what she earns part time at Wendy’s. In the same way, custodian Tonney Gazaway wants to attend college and upgrade a few parts of his life, but after he was laid off by the Fayetteville Public Library, he resorted to eating peanut butter sandwiches for every meal and doing odd jobs to earn enough to make ends meet.

The interviews conducted for class are people of all ages, races, and genders. They reveal that a lack of financial security can permeate all types of groups and demographics throughout Northwest Arkansas. While the bottom line for these people isn’t as low as it could be in other places, the fact that a number of individuals can struggle with money in an area loaded with Fortune 500 companies and high-paying jobs is revealing to the nature of economic groups in the area. Readers of the final project will get a sense of the types of people who are often forgotten amongst the cash-green shadows of Walmart, Tyson, and JB Hunt.

Overview essay, Katie Serrano

Twenty-five percent of families are considered to be in poverty in Northwest Arkasnas, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

While several factors can lead to poverty, one consistent issue brought up among individuals making less than around $23,000 a year was the state of Arkansas’s minimum wage.

Throughout this study, working poor individual’s have shown hope and promise about their futures, as well as a sense of pride in the work that they do.

Courtney Boyd, interviewed by Ann Johnson, spoke with a great sense of fondness about working at McDonalds, and was looking forward the future at a time when she would become a chef.

“I love cooking and being around food. That is one reason why I work here,” Boyd said in an interview with Johnson. “We are a tight knit group, like a family,” she said.

Boyd, who is also attending community college, said to Johnson that ultimately she is content with working at McDonalds for now because they are easy and flexible with her hours.

Throughout the reporting process, there has also been a vast variety in demographics. Data has shown that more single mothers in Arkansas are in poverty than any other group, and while the majority of the interviewed workers have been women, we have also seen diversity in race and background.

Mishell Quinter, interviewed by Andrew Epperson, is a Dreamer. Having an individual like this shows that poverty can affect any individual in this region, even those who came here specifically looking for a better way of life. Bertha Lara has been in America after living in El Savador since 1999 and has never seen a penny’s worth of a raise working for Tyson. These immigrants are hard workers, proven in their interviews, but have not been able to successfully support themselves with the wages they are given.

There are also individuals who, despite being in poverty, are still pursuing their passions. Carlos Morgan, a hairdresser interviewed by Aubry Tucker, hopes to one day own his own barbershop, and it appears that although things are tight for him right now, he is still doing what he loves and finds a passion in it.

All of these individuals put a face to an issue that is typically seen with prejudice or pity. When talking about individuals in poverty, people claim that if they just worked a little harder or went to school than they wouldn’t be where they are, but this process has showed that that is not the case. These individuals are still worthy of leisure time or things that will make them happy, like Cathy Lee who, in an interview with Mary Kerr Winters said that she spends the majority of her rent on going out with friends for a drink, video games and seeing drive-in movies despite being paid $11 an hour.

The working poor in Northwest Arkansas have shown pride in the work that they do, even if it is working for minimum wage at a McDonalds, Chuck E. Cheese or a local bar.

Bertha Lara, Poultry Worker, By Katie Serrano

For some individuals, even if they do have a job that pays what is deemed a “livable wage,” other factors can contribute to them falling below the poverty line.

Bertha Lara, a 52 year-old Tyson factory employee from El Salvador, has considered herself to be in poverty since she arrived in the United States and started working in 1999.

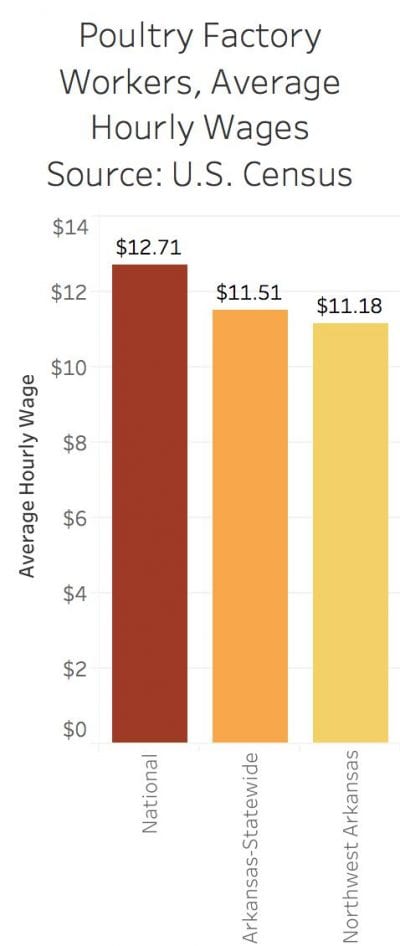

Despite still making $11.50 an hour, Lara, who now lives in Springdale, has struggled to support her family because of injuries on the job that keep her from working for months at a time.

“People have to borrow money to pay for their way here, so when you get here you arrive in debt,” she said. “Then you’re not paid enough, or not given a raise. I have been working their since 1999 and have never received a raise.”

Lara damaged the tendon in her left thumb cutting chicken, and the doctors took the tendon in her left ring finger out to fix her thumb, but now her left ring finger is having problems, she said.

This injury took Lara out of the workforce for eight months.

Listen below to hear Lara discuss what happened to her hands at the Tyson plant.

In order for Lara to continue working, she has to go see a specialist in Fayetteville to fix her hand, but she still hasn’t paid off her last doctor bills and can’t afford the new treatment.

“I’m concerned because I already have a left hand I can’t work with, so if I get surgery and mess up my right hand, I won’t be able to work,” she said. “After my first surgery they already wanted me to quit on my own, if I have to have another one they’ll find even more ways to pay me less.”

Lara is a member of the Northwest Arkansas Workers Justice Center, run by Magaly Licolli.

“We are just perpetrating this cycle of poverty, and if they can’t work they can’t contribute to the economy,” she said.

“Injuries cost money for the corporations. Its not just one case, its a repetition. Once they are fired, they don’t have any benefits and are out of the work force, entering this cycle of poverty,” Licollli said.

Despite their wage, Lara said that she has to live pay check to paycheck, if she is lucky.

Both Lara and her husband are still working to support their kids, who they hope will have a better future than themselves.

“Our children have seen all that we have been through and say to themselves, ‘We will make sure we get a good education so you don’t have to worry about us,'” she said.