Agenda for Monday, Oct. 8

–Context!

–Common Errors

Context #1

Add the Quick Facts for city population, demographics.

Little Rock: African American comprise 42 percent of Little Rock’s population. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/littlerockcityarkansas,US/PST045217

Add typical salary from Occupational Employment Statistics database for Arkansas

https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_ar.htm

Common Errors – Math

Percent vs Percentage Point

At Lyon College, 67 percent of non-first-generation students paid back their loans within five years, while only 53 percent of first-generation students did the same, which results in a 14 percent POINT difference. The median debt for both types of students was the same though, at $12,000.

You mean “percentage point.” 14 percent of 67 is 9.4.

Steve Doig – MathCrib-Doig

Common Errors – AP Style on Numbers

AP Style on Numerals:

Numerals – AP Stylebook-2avrxtn

Common Error – Divi Library

Divi Builder. Do Not Save to Library.

Context #2: Build Charts for Context

First row: The overall median debt for Arkansas students; for men, for women.

Second row: The overall median debt for first generation students. And non-first generation

Third row: The overall statewide repayment rate, and the rate for men, for women

Fourth row: The overall median debt for white, black, asian, hispanic

Post on WordPress with the category Context

Research – Data Question

The Financial Aid department does not report loan repayment info to the Department of Education. “Once the students leave us we don’t track their information anymore,” he said.

Question: Look at data dictionary for source of this information. All 1,826 columns explained here.

https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/assets/FullDataDocumentation.pdf

https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/assets/CollegeScorecardDataDictionary.xlsx

Homework

#1: Read this report and compare to your work on context. Prepare to discuss it Wednesday

https://ticas.org/sites/default/files/pub_files/classof2016.pdf

#2: By 11:59 p.m. Tuesday, fix the issues with your charts and stories from Assignment #2. Post on WordPress, use the Context category for a tag

Thomas Mandrell, Walgreens. By Mary Kerr Winters

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – Walgreens’ designated hitter, Thomas Mandrell, 23, works full-time stacking toilet paper, peanut butter, and filling in wherever needed around the store. He makes $12.85 an hour, which is a monumental step up from the $7.75 he made working at Popeye’s.

Mandrell said it was a tough battle trying to get by on that slim of a budget while working as a server at Popeye’s. Most of his money goes towards rent, car coverage, and savings. Walgreens offers its employees a well-rounded insurance policy and “after each evaluation, employees are offered a 20 percent raise, which is what is really cool about working here,” Mandrell said.

The difference between Designated Hitters and regular Walgreens employees is that they are allowed to go back into the pharmacy and fill prescriptions.

Mandrell moved to Fayetteville when he was 13 years old with his family while the rest of his family remains in Arlington, Texas. He said, “the white side of his family is still here and the Hispanic side is in Texas.” He is saving up money to move back to be a Spanish translator for his family so that they will be able to have more work opportunity and to have better connection with family members.

One of the main struggles Mandrell deals with is the language barrier between him and his family. Mandrell said this language disconnect limits his family members from work opportunities, which is why he strives to be a translator for them.

“Working at Walgreens is a really good job. It is very stable and something I can always depend on,” Mandrell said. His prior experience working at Popeye’s gave him a wide skill set that Mandrell said he believes helped him get his current job, and allowed him to move up in the company quickly.

When asked about the stress difference between working at Popeye’s and working at Walgreens, Mandrell said no matter what position you hold that it is incredibly stressful. He got his current job through a family connection, which he expressed an immense amount of gratitude because it got him out of his prior job.

Mandrell is very musically motivated, and enjoys playing the guitar in his free time. He said he likes to spend his extra cash on meaningful tattoos, and “hopes to have full sleeves on both arms one day.”

The tattoo on his left forearm is his “tree of life.” It symbolizes all of the things that motivate him and express his personality and values. This is why there are musical notes hanging from the leaves.

Even though he described the benefits of Walgreens as great, he does not want to do this forever. He is interested in getting involved in working with the law in his future back in Texas.

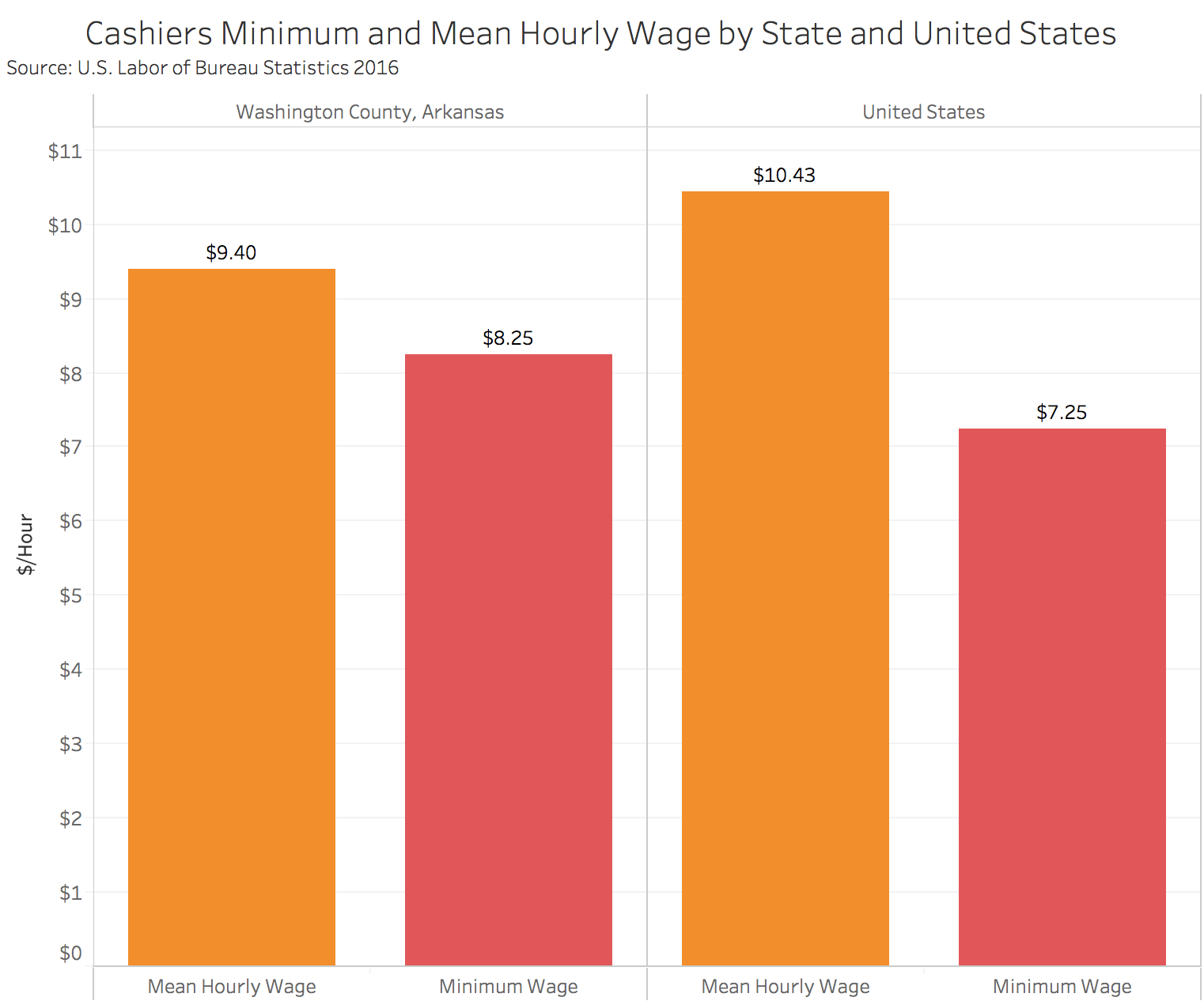

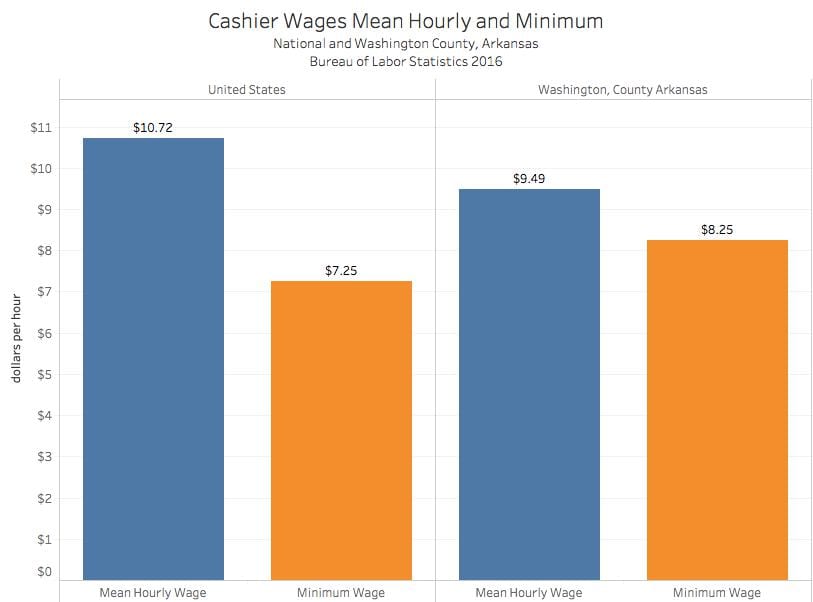

This chart displays that minimum wage is less than what the hourly wage is, meaning people making more the minimum amount can still be classified as working poor.

Karen Roquemore, Harp’s. By Aubry Tucker

Karen Roquemore, 48, works two jobs to keep up with her lifestyle. Her full-time job entails pushing paperwork, and answering calls mostly for commercial insurance clients. She’s been with this company for 18 years and makes $15 an hour. Roquemore said she had to pick up a second job, because her office job was no longer able to offer overtime for her or any of her coworkers. Her full-time job takes absolutely no more than 40 hours a week, and she said she supplements with a cashier position at Harps Grocery Store. Her position as a cashier pays $10 per hour. Roquemore is wearing her black Harps uniform and she has a big, inviting smile on her face. She said she is happy to work at Harps even part-time, because it doesn’t take too much energy and they don’t ask for too much out of her. “I make enough to make it worth my while,” she said. The flexibility is what she said she likes most about her cashier job at Harps.

Roquemore is married, but her and she husband have no children. She said that it would be even more difficult to maintain a comfortable lifestyle if she had kids to take care of too. She said there’s probably no way she could work two jobs like she does if she added children to the mix. She said she has some spending habits and that she has a weakness for purses. Roquemore is very independent, she says her husband is able to give her what she needs, but things that she wants are up to her. “When I go home, it’s just me and my dog,” Roquemore said she and her husband are often on different schedules.

Roquemore said her job with the General Agency is more stressful than her job as a cashier at Harps. Her position with the agency doesn’t offer a 401-K, but another type of “stock-like” retirement that fluctuates with the performance of the department. She said it is similar to a 401-k, but her retirement does not compound.

Roquemore said her husband gets tired of her working two jobs and that it can be a stress on their relationship. However she says it’s worth it to give more of her time to a job in order to have more flexibility in her budget. “A girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do…I’m physically capable of working 2 jobs, so I’m okay.” she said.

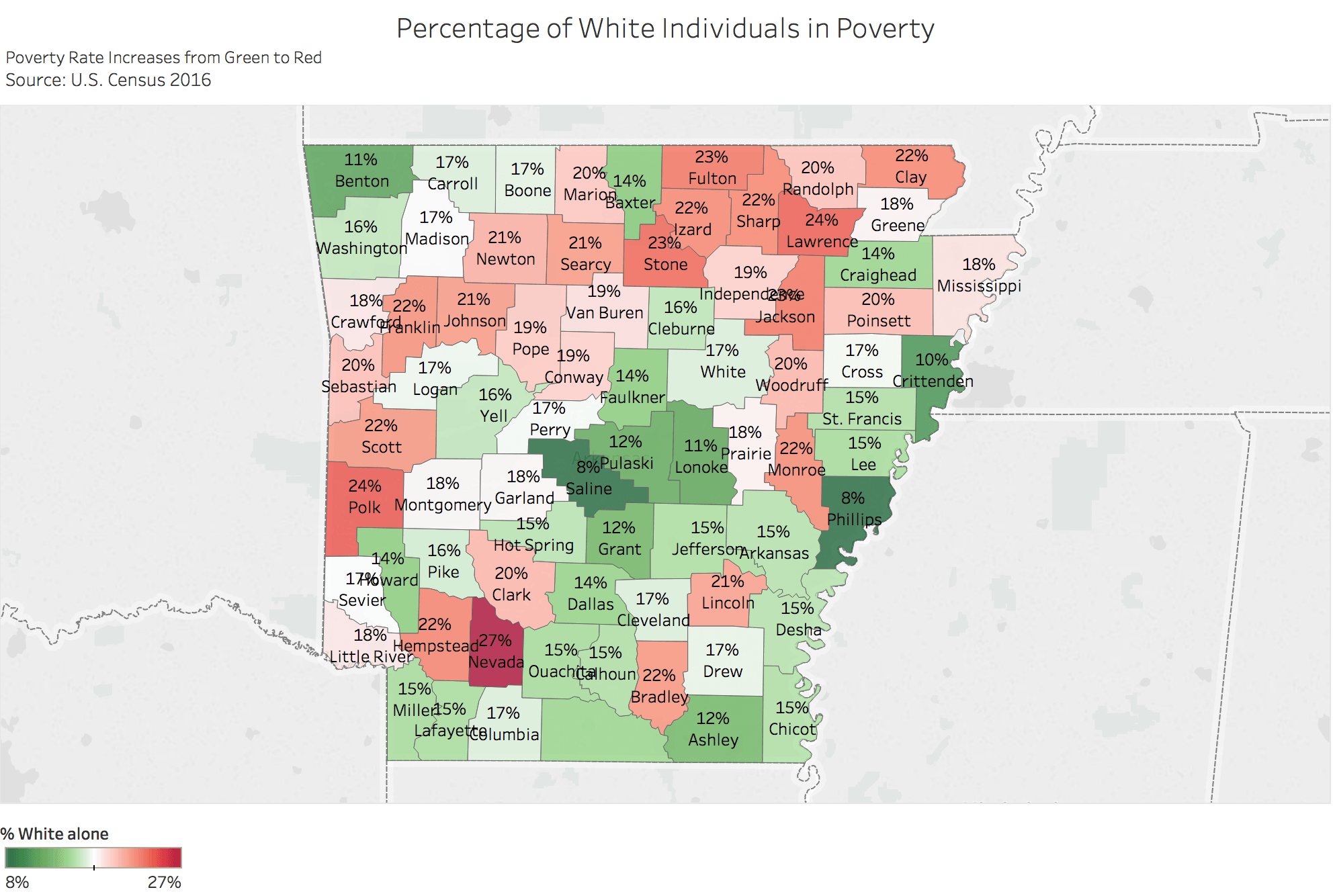

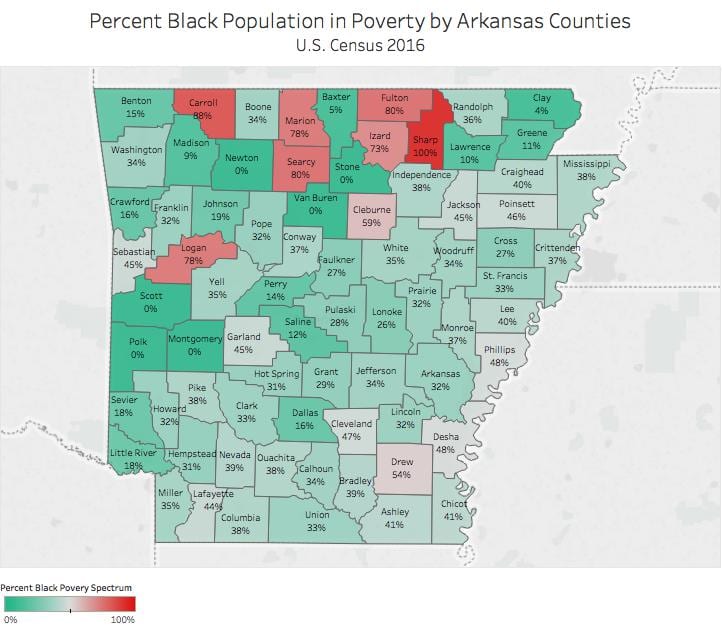

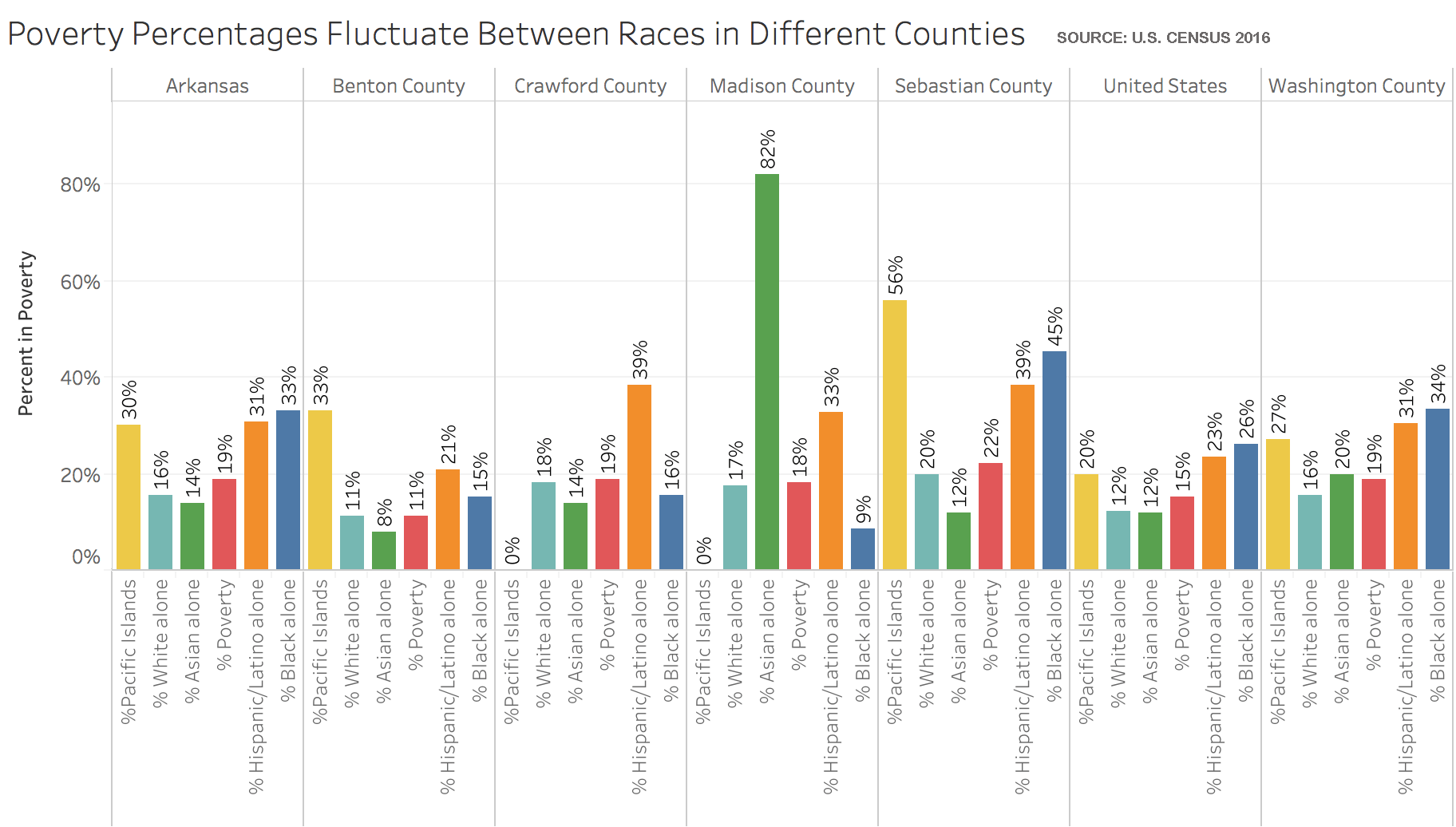

The following map of Arkansas is broken down by county, illustrating the most at-risk black communities to be in poverty. Sharp county has a 100% poverty rate in the black community, but the total number of blacks in poverty is only 11.

Version 2

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Karen Roquemore, 48, works two jobs to keep up with her lifestyle.

Her full-time job for General Agency Company, an insurance firm, entails pushing paperwork and answering phone calls mostly from commercial insurance clients. She’s been with this company for 18 years and makes $15 an hour. Roquemore said she had to pick up a second job as a cashier at the grocery store Harps when her office job quit offering overtime.

At Harps, Roquemore earns $10 per hour. Wearing a black Harps shirt and an inviting smile, Roquemore said she is happy with the part-time job at Harps. It doesn’t take too much energy, they offer flexibility and don’t ask for too much out of her. “I make enough to make it worth my while,” she said.

Roquemore said her job with the General Agency is more stressful than her job at Harps. But General Agency offers a retirement savings plan that is similar to a 401(k) plan.

Roquemore is married but she does not have children. It would be even harder to maintain a comfortable lifestyle with children in the mix and she certainly could not juggle two jobs. Roquemore aid she has some spending habits and that she has a weakness for purses. Roquemore is very independent, she says her husband is able to give her what she needs, but things that she wants are up to her. “When I go home, it’s just me and my dog,” Roquemore said.

She and her husband are often on different schedules and her two jobs can be a stress on their relationship. However, she says it’s worth the stress to have more flexibility in her budget. “A girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do…I’m physically capable of working two jobs, so I’m okay.” she said.

Blogpost 2/28 – Andrew Epperson

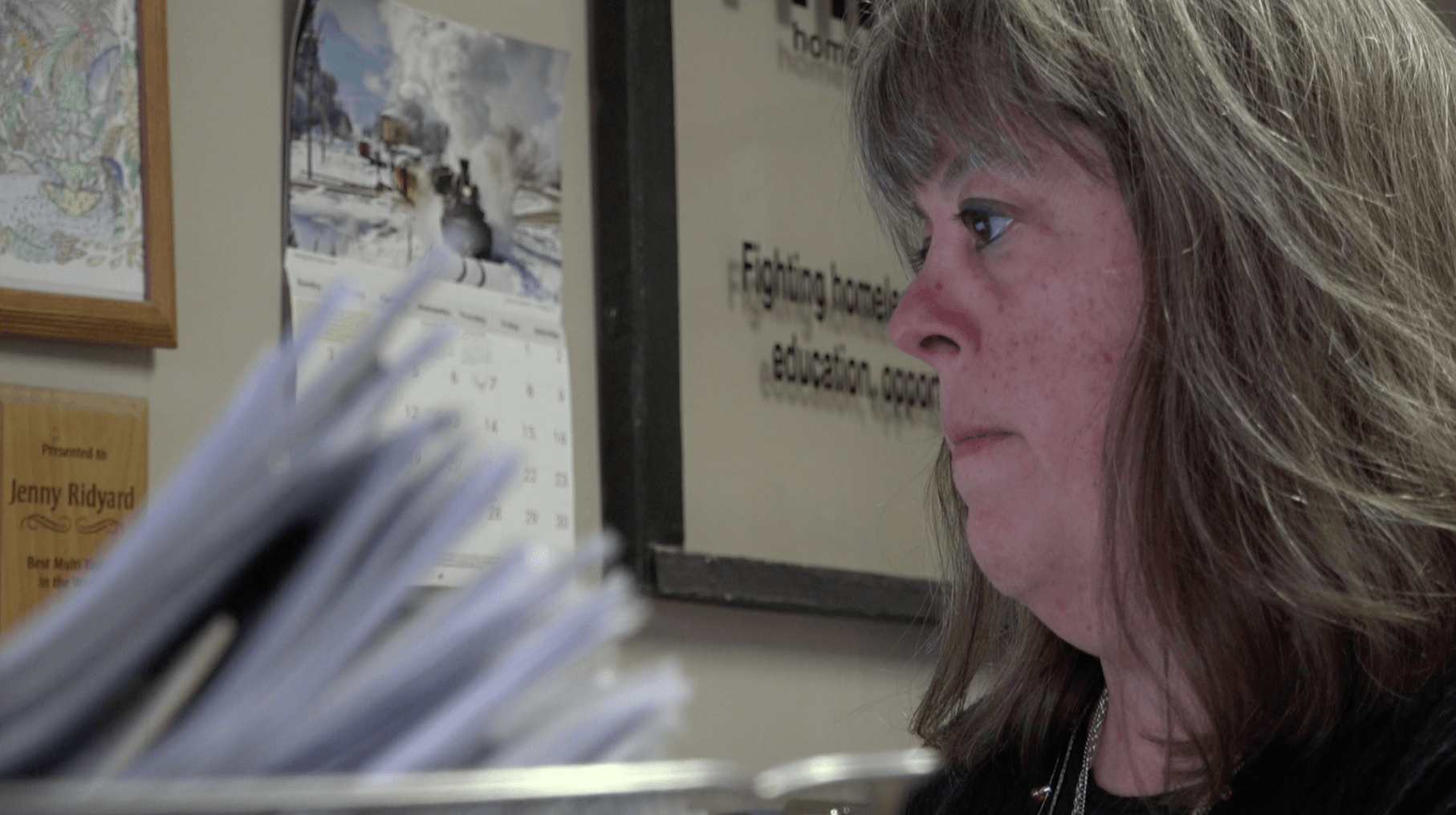

Jenny Ridyard, a client service specialist and data entry worker for 7Hills Homeless Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas, experienced an extreme form of poverty. In fact, she and her husband were homeless for seven months before she landed her position with 7Hills.

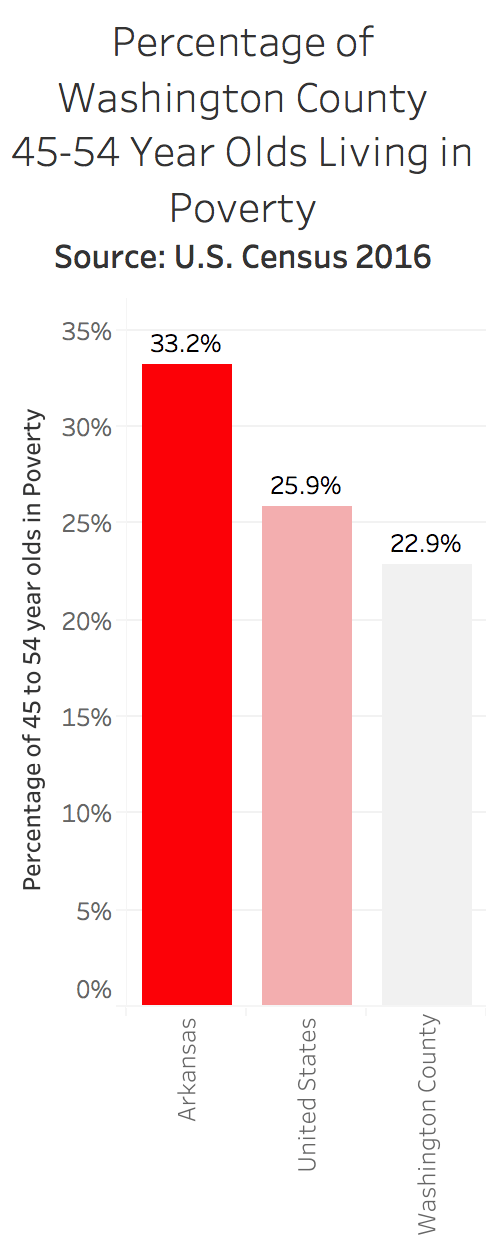

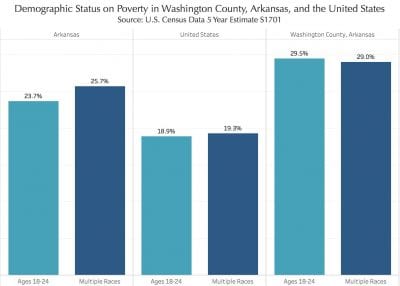

According to statistics collected in the U.S. Census, there is a fewer percentage of people Ridyard’s age impoverished in Washington County compared to the state and the country.

Though it’s easy to get caught up in the statistics, there is still a large number of people in the county who live in poverty, Ridyard said.

At that time in her life, Ridyard’s income was $0. Her husband has Parkinson’s disease, and he lost his job as a forklift operator when his ailment increased to a point where he could no longer operate the controls. The Ridyards applied for disability, but they had to wait a significant amount of time for that money to start rolling in. They began living out of a tent, and 7Hills became an important resource for them, as they supplied needed medication and meals.

When Ridyard’s husband’s disease continued to accelerate because of his poor living conditions, he was fast tracked to a seven-month wait, she said. During that time, the Ridyards ate at churches and continued to frequent 7Hills and the Salvation Army.

Around the same time Ridyard’s husband began receiving his disability checks, an intriguing opportunity opened up for her. Because of her familiarity with the homeless community and her good standing within the 7Hills community, she was asked to apply for an open job in the client service and data realm within the center.

Ridyard was hired, but when she looks back on it, a part of her never thought she’d make it out of the woods, she said.

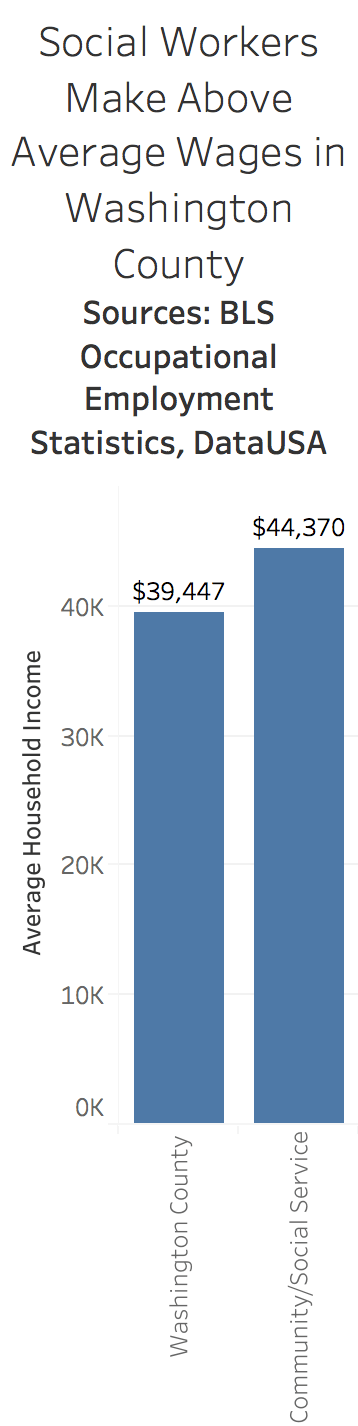

According to statistics from the BLS Occupational Employment Database, jobs listed under “Community and Social Service” make an average of $44,370 a year. Careers and jobs involving homeless outreach are at the low end of the totem pole, so one could speculate Ridyard makes significantly less than that. If taken at face value, that type of job makes more than the average Washington County resident.

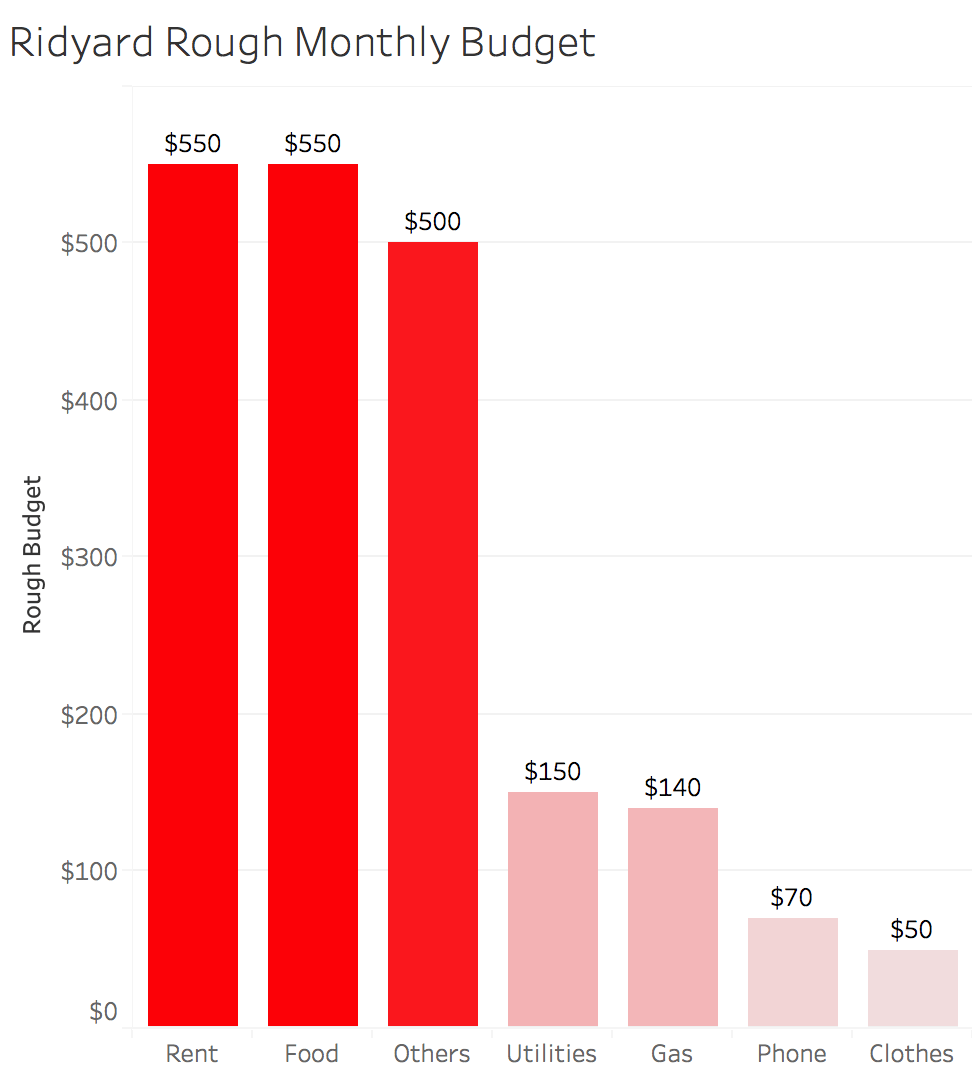

If Ridyard’s supposed $44,370 salary was divided up, she’d make around $3,697.50 per month. If that were the case, she’d be making much more than what her rough monthly budget could be.

According to the Census ACS Survey conducted in 2015, Fayetteville’s average monthly gross residential rent is $749. She lives in a one-bedroom apartment, but she’s hoping to move into a house within the next year, she said.

By opening up a savings account and actively saving with the intent to buy a small house, Ridyard hopes she can learn from her time in extreme poverty but never live in it again, she said.

Abigail Jobst, Server. By Elisabeth Butler.

Approximately one-in-three residents of Fayetteville fall below the poverty line. Alejandro Zeballos and Abigail Jobst were among those who struggled with that fate.

Jobst, 24, originally from St. Louis, waited tables at Grubs Uptown for most of college. Even though she no longer works there, the experience showed her what poverty was like. As a journalism student at the University of Arkansas, it was easy to balance school and work. She had to support herself after her parents stopped giving her the little they did. In 2015, Jobst met Zeballos, and they married in December of 2016. In the summer of 2017, Zeballos, an immigrant from Bolivia, lost his education visa, forcing him to lose his job at a marketing firm.

For close to six months, the married couple lived off of a servers salary alone. Being a server is inconsistent at best – especially at this location. Some nights, Jobst would leave with $350 in cash, and some nights she would leave with $19.

“I had to balance giving up things I love,” Jobst said.

Beyond the financial instability that comes with being a server, there was emotional instability as well.

Most graduates expect to get a job immediately after graduation. The majority of Jobst friends achieved jobs with salaries in the five-figures soon after leaving college, and she didn’t. This left her feeling unaccomplished and emotionally behind. Jobst did not get a job until almost a year and a half after graduation. Recently, Jobst accepted a position with the Girl Scouts of America where she is a recruitment supervisor.

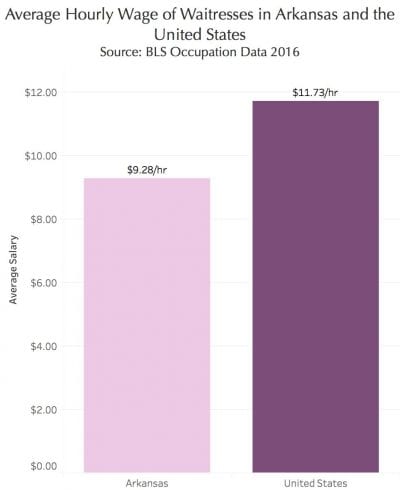

For most college students and recent graduates, a job like serving is very common. The hourly wage for servers in Arkansas is lower than that in the United States as a whole. When this is the primary salary, that person immediately falls below the standard of living.

Luckily for Jobst, Zeballos had a job that brought in nearly $50,000 each year. But when his immigration paperwork failed to go through, Zeballos lost his visa, and as a result lost his job. Jobst speaks on the immediate shock of the loss, and what they had done to prepare.

Luckily for Jobst, Zeballos had a job that brought in nearly $50,000 each year. But when his immigration paperwork failed to go through, Zeballos lost his visa, and as a result lost his job. Jobst speaks on the immediate shock of the loss, and what they had done to prepare.

When the couple married in 2016, they knew that the deadline was coming soon to extend the work visa. They blame their predicament on how late the documents were submitted. They spent what money they had left to pay for an immigration lawyer and print documents. They spent hours making sure everything was accurate, and “printed, labeled, and put together”, Jobst said.

Seven months passed before any kind of court date, until late October 2017. Zeballos gained his green card back, and went back to work almost immediately at the marketing firm. Jobst and Zeballos were not alone in their poverty status In Washington County, Arkansas, nearly 30 percent of residents aged 18-34 remained under the poverty level. For multi-ethnicity households, that percentage is 29%.Jobst and Zeballos met both of these criteria while living on a servers salary.

During their time below the poverty line, Jobst and Zeballos were among the statistic of multiple ethnicity households that were in poverty. The struggles of being newlyweds and living under the poverty line bring on a set of struggles.

Not only are the struggles financial, but they are also emotional. Their relationship took a toll because of the many negative factors that come with being unemployed and poor.

“That was the least close we had been,” Jobst said.

The security of having a job, a steady income, and financial stability are not only meaningful for young couples, but also necessary.

Assignment #2- Katie Serrano

For a family of two living in Fayetteville, Arkansas making less than $24,000 a year, their monthly budget is nearly half of what the Internal Revenue Services considers to be the proper standard of living.

For Lisa Terry, 23, and her husband, their household rent is $200 less than the median for Fayetteville, and they live pay-check-to-pay-check.

“I make minimum wage working at Waffle House, and my husband works in Facility Management at the University,” Terry said. “We consider ourselves working poor. Thankfully my husband gets paid monthly, and we use that paycheck on bills, food and gas.”

Terry and her husband eat “cheap food like spaghetti, and ramen,” and she said that she is lucky because Waffle House allows her to eat one free meal for every four hours she works.

Waiters and waitresses in Washington county and the Northwest Arkansas area make roughly 20 percent less annually than the national average wage.

“The minimum wage for waitering in Arkansas is $2.63, and Waffle House tries to compensate if your tips don’t make up the difference to $8.50, but it’s not nearly enough to get by,” Terry said. “If I’m able to work around 35 hours a week, I’m lucky.”

She has tried to get other jobs, but always ends up back at Waffle House, where she has been working since May of 2016.

“I had to drop out of school because of a medical issue,” Terry said. “Whenever I go apply for other jobs nobody wants to hire someone who wants to work as many hours as me. They want to hire high school or college students who only want to work twenty or so hours a week so they don’t have to pay them benefits.”

Nineteen percent of individuals between the age of 18 and 34 are considered below the poverty line in Washington County, which is 5 percent higher than the national average for that age group.

Lisa Terry, 23 from Fayetteville, Arkansas

The standard housing budget for a couple in Fayetteville is 97 percent lower than the standard set by the IRS, while the monthly food budget is 54 percent lower than it should be.

Although these occupations pay barely enough to get by, 2.5 million individuals fill the positions nationwide, and a little over 4,000 individuals are employed in these positions in Northwest Arkansas alone.

Questions for Jon Schleuss – Aubry Tucker

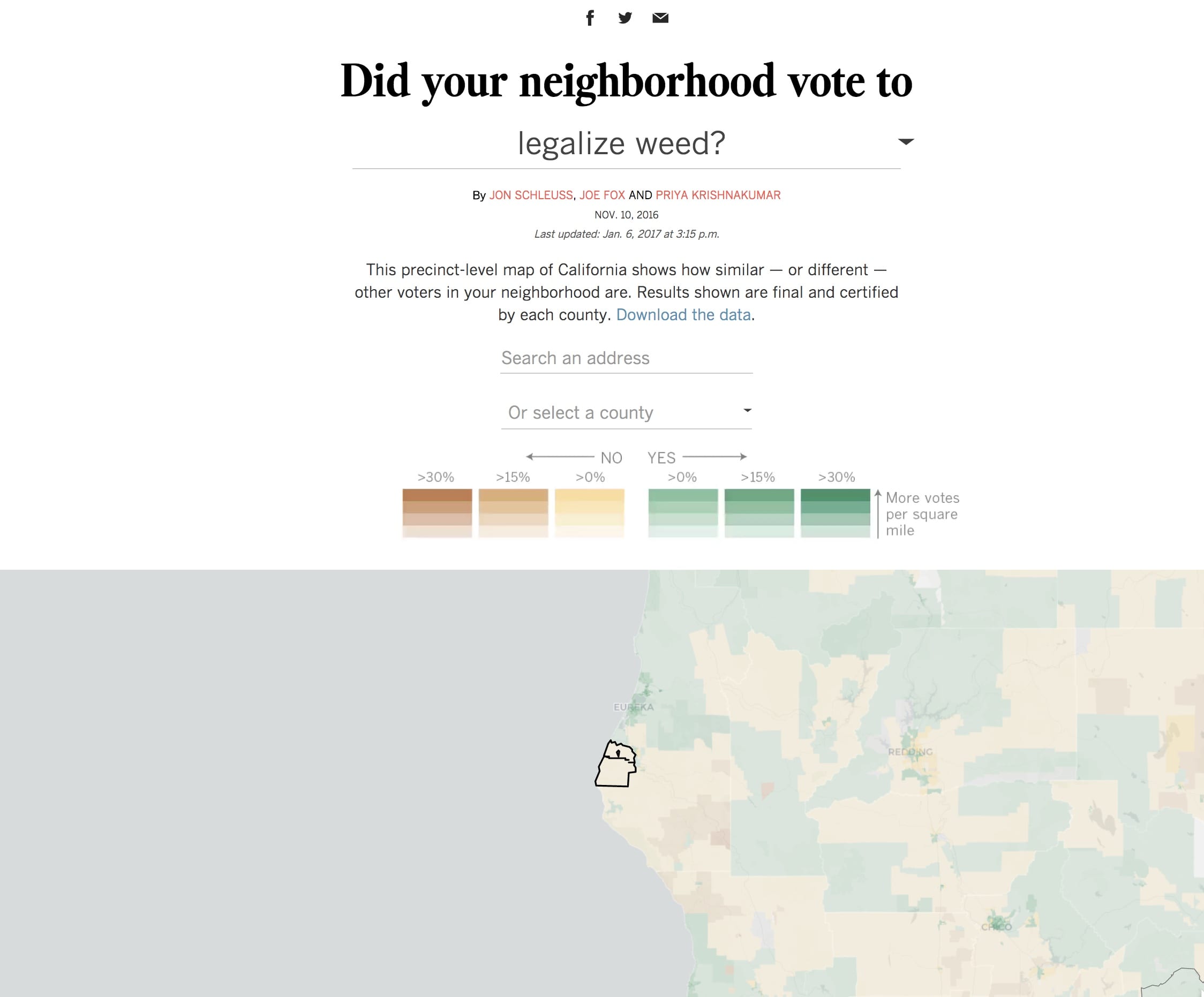

What does coding mean to a journalist, what kind of things are you accomplishing in coding? What in your background was helpful/fitting that led you to data journalism? How do you remain objective, and not lead the data to what you want to portray?

Class 7: March 1, 2018

Jon Schleuss

Katie Serrano

https://wordpressua.uark.edu/datareporting/assignment-1-katie-serrano/

Andrew Epperson

https://wordpressua.uark.edu/datareporting/blogpost-for-2-14-andrew-epperson/

Other students:

Ann Johnson

https://wordpressua.uark.edu/datareporting/assignment-1-with-revisions-ann-claire-johnson/

Aubry Tucker

https://wordpressua.uark.edu/datareporting/aubry-tucker-assignment-one/

Mary Kerr Winters

https://wordpressua.uark.edu/datareporting/mary-kerr-winters-assignment-1-census-data/

Questions for Jon Schleuss – Mary Kerr Winters

Have you always desired to be a data journalist or did you have another route in mind? If so, how did you learn to adjust when first starting data journalism? What are some surprising ways your skill set of coding, graphic design, data journalism, photoshop, etc. have helped you in other areas of your life?

Tell us about a time you messed up when coding or displaying data (if there was a time), and what you did to recover it so that we can know what to do in these times.

Questions for Jon Schleuss – Butler

- How does one take seemingly meaningless data and turn it into something that will tell a story to readers?

- How do you turn data into more than just a few pictures?

- How much of a research component is there to presenting data in an effective way. I’m Ad/PR, so I immediately think of things like target market, and segmentation, and presenting it to each group in a proficient way; is that a real thing?

Questions for Jon Schleuss – Andrew Epperson

- As a UA graduate, what were the steps you had to take to get your foot in the door with a publication as prestigious as the LA Times? As a second part to that question, did it take some time to feel confident among journalists who graduated from more “prestigious” institutions?

- Are you currently working in your dream job, and if not, what would you like to ultimately do?