effects of literariness on reading

The relatively-new, online, open-access (with access potentially to even the reviews, an option authors may select at the time of submission) journal Collabra published in December a fascinating paper by van den Hoven et al. reporting the effects of literariness on reading behavior. The main research question is whether literariness (sometimes called foregrounding), in the form of a change in style (e.g., alliteration, metaphor), has a measurable impact on how readers process text. One potential purpose of foregrounding (I’m leaning heavily on Miall & Kuiken’s [1994, Poetics] paper here) is disrupt typical communication, which is highly automatized, to lead to de-automization. To the extent that the surface structure of language is typically primarily a route to meaning (text is the medium, not the message) — which is where we’d usually like to get to when processing language — disrupting typical processing via foregrounding should lead to additional focus on surface structure (e.g., the precise words, their sounds, etc.), which theoretically could lead to aesthetic appreciation.

This was a two-stage project. The first involved asking a group of 16 young adults (a sample small enough to give pause to my honors student; she’s not wrong to worry) to read three short stories twice; during the second pass through the story, each participant was asked to underline all words, sentences, and passages that they considered “literary”. The result of this exercise was that every word in each story had a 0-to-16 literariness score. The judgments of these (presumably) non-experts were fairly strongly correlated with those of an expert (one of the co-authors, a rhetorician).

In the second stage of the research, another group of young adults (n = 30 this time) read the same stories while their eye-movements were tracked. After reading, participants also rated their immersion in and their enjoyment of each story; they were also later given a recognition  test to examine whether literary, foregrounded elements were remembered better than non-foregrounded elements of the text; nothing much emerged here. The eye-movement data allowed the researchers to estimate the impact of literariness alongside a host of other variables known to influence reading time (e.g., word frequency & length; perplexity, or how surprising a word is). The first of several interesting findings appears in the figure at left (shared because open access!). The dots are point estimates (along with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals) for the effect of different variables on reading time (as indexed by gaze duration); points to the right of the vertical line are positively related to how long it takes to read a word (e.g., word length –> longer word, longer reading time), and those on the left are negatively related (e.g., frequency –> higher frequency, shorter reading time). Of most interest is the effect of literariness: the more literary a word was (rated), the longer it took to read. This in itself is not a novel finding, but the use of eye-tracking is a nice contribution, as is the replication of prior findings.

test to examine whether literary, foregrounded elements were remembered better than non-foregrounded elements of the text; nothing much emerged here. The eye-movement data allowed the researchers to estimate the impact of literariness alongside a host of other variables known to influence reading time (e.g., word frequency & length; perplexity, or how surprising a word is). The first of several interesting findings appears in the figure at left (shared because open access!). The dots are point estimates (along with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals) for the effect of different variables on reading time (as indexed by gaze duration); points to the right of the vertical line are positively related to how long it takes to read a word (e.g., word length –> longer word, longer reading time), and those on the left are negatively related (e.g., frequency –> higher frequency, shorter reading time). Of most interest is the effect of literariness: the more literary a word was (rated), the longer it took to read. This in itself is not a novel finding, but the use of eye-tracking is a nice contribution, as is the replication of prior findings.

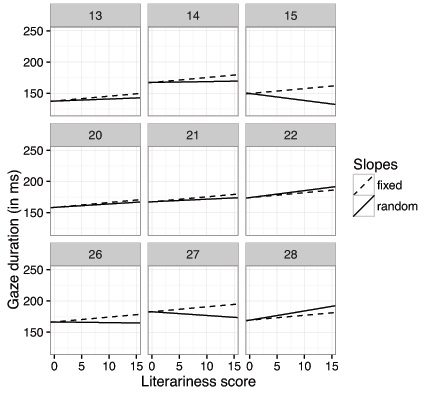

But the likely biggest contribution of this research is the examination of individual differences in sensitivity to literariness. By estimating a slope (i.e., the relationship between literariness/foregrounding and reading time) separately for each of the 30 readers in the study, the researchers are able to make a more-nuanced point about the effect of literariness: it’s not the same for everyone. The solid lines in the figure at right (cropped from the original, and linked to the full version of the original) gives a sense of how some of the different readers responded to literariness. Some show a clear increase in reading time with greater foregrounding, whereas others show a decrease. This is one of the benefits of estimating regression models that allow slopes to vary across individuals, rather than assuming that every individual shows the same, fixed effect (i.e., the dashed line in the graphs). Another benefit of estimating different slopes for each subject is that this allows one to try to understand the factors that are causing (or at least are related to) the differences in slopes. In the current paper, no aspect of immersion or story enjoyment was strongly related to the effect of foregrounding, which I expect was a disappointment to the researchers (it is to me), but the effect of perplexity (i.e., how unexpected a word is) on each participant’s reading time was strongly predictive of the effect of foregrounding; that is, readers who showed a greater perplexity effect (i.e., slowed down more due to unexpectedness of words) were also more sensitive to foregrounding (i.e., showed a positive slope in the figure at right). This feels like fertile ground for research, trying to understand what literariness is both apart from and as a consequence of perplexity.

But the likely biggest contribution of this research is the examination of individual differences in sensitivity to literariness. By estimating a slope (i.e., the relationship between literariness/foregrounding and reading time) separately for each of the 30 readers in the study, the researchers are able to make a more-nuanced point about the effect of literariness: it’s not the same for everyone. The solid lines in the figure at right (cropped from the original, and linked to the full version of the original) gives a sense of how some of the different readers responded to literariness. Some show a clear increase in reading time with greater foregrounding, whereas others show a decrease. This is one of the benefits of estimating regression models that allow slopes to vary across individuals, rather than assuming that every individual shows the same, fixed effect (i.e., the dashed line in the graphs). Another benefit of estimating different slopes for each subject is that this allows one to try to understand the factors that are causing (or at least are related to) the differences in slopes. In the current paper, no aspect of immersion or story enjoyment was strongly related to the effect of foregrounding, which I expect was a disappointment to the researchers (it is to me), but the effect of perplexity (i.e., how unexpected a word is) on each participant’s reading time was strongly predictive of the effect of foregrounding; that is, readers who showed a greater perplexity effect (i.e., slowed down more due to unexpectedness of words) were also more sensitive to foregrounding (i.e., showed a positive slope in the figure at right). This feels like fertile ground for research, trying to understand what literariness is both apart from and as a consequence of perplexity.

One thing that’s missing from this paper, and perhaps the literature on literariness/foregrounding/defamiliarization more generally, is attention to work by Murphy and Shapiro (1994, Memory & Cognition) and others on memory for verbatim, surface information. In the introduction to their paper, Murphy and Shapiro argue that “in most cases, listeners are interested in the content of the conversation, and that is where they allocation their attention. However, when the exact wording of a sentence has crucial implications for the goal at hand, it may receive as much attention as the meaning of the sentence, and as a result, it may be well remembered” (p 87). For the sake of fairness, I should point out that M&S did not make an effort to incorporate literariness or foregrounding into the reasons why a person might shift attention to surface form more than is typical. There may be findings in this older literature that could inform studies of the influence of literariness.

Despite this, this newly-published research on literariness is excellently executed and analyzed, fascinating in its results, and is presented with admirable thoroughness. Credit for this is due not only the authors but also to the editors (Rolf Zwaan and Jeffrey Zacks) and the reviewers, as well as the powers that enabled Collabra to be a thing.

(some) spoilers spoil stories

In 2011, Leavitt and Christenfeld reported (PDF link to original paper) – to much, much, much media attention – that presenting a spoiler before a short story increased enjoyment of that short story, counter to the intuitions of many. Although this research was conducted on the usual college-students sample, the sample was very large (over 800) and the findings pretty convincing, as 11 of 12 stories got some boost in enjoyment from a spoiler. (And it turned out that Leavitt and Christenfeld got similar results reported in another paper [PDF link to original], although there they reported a few nuances to the general spoilers-improve-things finding.)

My lab reading group read and I discussed this research pretty shortly after it was published. My then-grad student, Kevin Autry, argued that the results might not generalize beyond stories that people had no prior investment in. That is, if you spoil a story that someone has no prior interest in, maybe it will make the story more enjoyable. This is not at all the same thing as spoiling a story that someone has been waiting years for (e.g., the latest Star Wars installment) or that someone has seen all but the latest episode of. This idea kicked around the lab for a while, and finally in summer 2014, my then-honors student, Michelle Betzner, and I decided to do an experiment testing whether spoiling stories after someone cared about them (i.e., in the middle of the story) was ruinous. And we also thought it was a good idea to see if Leavitt and Christenfeld’s (2011) original findings were replicable. As of that summer, there were no published reports that we could find of even an attempted replication.

The details of what we found are reported in a paper just accepted (PDF link to the accepted manuscript) for publication in the journal Discourse Processes. The short version is that we found that spoilers reduced enjoyment of stories. Our stories were different than those used by Leavitt and Christenfeld, and our spoilers were shorter and quite blunt. But it’s not probably not the shortness of the spoilers that led to the different results; Johnson and Rosenbaum – independent of my lab’s work – were doing a very similar experiment with longer spoilers, and found that spoilers reduced enjoyment of stories (press release; PDF link to manuscript). Our findings and those of Johnson and Rosenbaum are not that surprising, but in light of Leavitt and Christenfeld’s findings, they open the door to interesting questions about what kinds of spoilers may do different things to readers’ enjoyment.

Recent Comments